BITE ON

Seventy years ago this week, Orange County’s most brutally suppressed strike began with a bite.

On June 15, 1936, at the break of dawn, about 200 Mexican women gathered in Anaheim to preach the gospel of huelga—strike. Four days earlier, about 2,500 Mexican naranjeros representing more than half of Orange County’s crucial citrus-picking force dropped their clippers, bags and ladders to demand higher wages, better working conditions and the right to unionize.

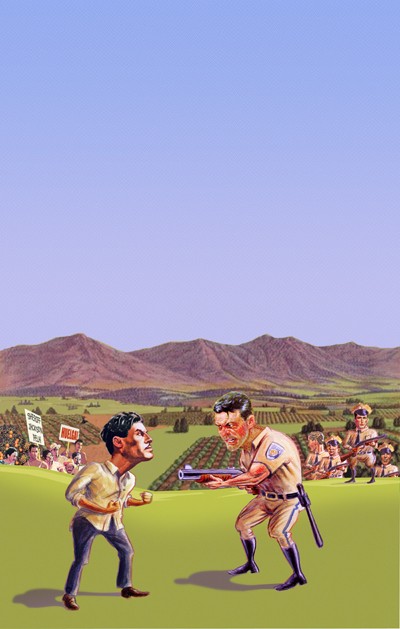

The women spread across the groves of Anaheim, the heart of citrus country, urging workers to let the fruit hang. Twenty Anaheim police officers confronted the women; they refused to disperse. At some point there was an altercation, and 29-year-old Placentia resident Virginia Torres bit the arm of Anaheim police officer Roger Sherman. Police arrested Torres, along with 30-year-old Epifania Marquez, who tried to yank a strikebreaker—a scab—from a truck by grabbing onto his suspenders.

Little else is known about the Fort Sumter of Orange County—newspaper accounts say only that Torres and Marquez received jail sentences of 60 and 30 days, respectively. But Orange County responded with an organized wrath years in the planning. Growers enlisted the local chapters of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and American Legion to guard fields. They evicted families of strikers from their company-owned houses. The English-language press became a bulletin board for the growers—The Santa Ana Register, for instance, described the 200 Mexican women in Anaheim as “Amazons with fire of battle in their eyes.”

Orange County Sheriff Logan Jackson deputized citrus orchard guards and provided them with steel helmets, shotguns and ax handles. The newly minted cops began arresting strikers en masse, more than 250 by strike’s end. When that didn’t stop the strike, they reported workers to federal immigration authorities. When that didn’t work, out came the guns and clubs. Tear gas blossomed in the groves. Mobs of citrus farmers and their supporters attacked under cover of darkness.

What county residents tried to dismiss as a fruitless strike quickly escalated into a full-fledged civil war in which race and class were inseparable. The Mexicans of Orange County, the county’s historical source of cheap labor, were finally asking for better working conditions; their gabacho overlords wouldn’t hear it. And so both sides fought for a month until the lords of Orange County won.

Wonder why Orange County trembles whenever its Mexicans protest? Welcome to the Citrus War of 1936, the most important event in Orange County history you’ve never heard of.

PICKING A FIGHT

The Citrus War erupted at a volatile point in California and Orange County history. It was the nadir of the Great Depression, and radicalism was in the air. Two years earlier, writer Upton Sinclair nearly became California’s governor by campaigning under the slogan EPIC (End Poverty in California). Blood spilled across the fields of the Golden State as law enforcement and growers joined to brutally suppress unions. It was the year crusading journalist Carey McWilliams of the Pacific Weekly wrote a series of exposés about California’s agricultural industry that he would publish three years later in his classic Factories in the Field.

Orange County was a bucolic exception to California’s troubles. Its 51 orange-packing houses and more than 5,000 growers carefully crafted a national image of Edenic stability. Gorgeously decorated crates with labels such as Altissimo, Esperanza and Miracle portrayed a mythical California in which the Pacific Ocean gave way to orange groves that swept up to the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains; every crate of oranges offered paradise to a weary nation.

The country rewarded Orange County for its dreamscape; the Orange County citrus industry brought in $20 million in 1938 alone. “By the blessing of nature, Orange County had the lion’s share of the summer crop [of oranges] when the consumer was thirstiest,” wrote UC Irvine professor Gilbert G. González in Labor and Community: Mexican Citrus Worker Villages in a Southern California County, 1900-1950, his 1994 history of Orange County citrus pickers. At its height, 75,000 acres of Valencia orange groves covered the county, mostly in Brea, La Habra, Anaheim, Orange, Villa Park and sections of Irvine.

Growers depended heavily on seasonal Mexican laborers, who brought with them a memory of unionism. In 1928, according to González, 14 Orange County residents participated in the first Southern California chapter of the Confederación de Uniones Obreras Mexicanas (Confederation of Mexican Workers Unions, or CUOM), a union for Mexican laborers in the United States organized through the Mexican consulate; the Great Depression soon smashed CUOM, and an alternative union emerged: the Confederación de Uniones de Campesinos y Obreros Mexicanos (Confederation of Mexican Farm Workers’ and Laborers’ Unions, or CUCOM). Whereas CUOM reported directly to the Mexican government, CUCOM’s founders had their roots in the Industrial Workers of the World, better known as the Wobblies, one of the most powerful and most radical unions of the 1920s.

[

Under the direction of William Velarde, CUCOM led one of Orange County’s first strikes in 1933, when 125 Laguna Beach vegetable pickers left their jobs demanding 30 cents an hour. CUCOM organized other successful strikes in Orange County’s celery, squash, pea and lettuce industries, and Orange County’s naranjeros—who made up the bulk of Mexican laborers in the county at the time—took notice. On Oct. 11, 1935, Mexican consul Ricardo Hill told more than 2,000 citrus pickers at Anaheim’s Pearson Park that the consulate would support the naranjeros in their struggles for better wages. By the end of 1935, CUCOM set its sights on King Citrus.

'THE THREAT OF VIOLENCE'

On March 18, about a month before the start of the Valencia orange harvest, CUCOM organizers presented growers with the demands of Orange County pickers: 40 cents per hour for an eight-hour work day instead of 27 cents; free transportation and tools; the abolition of a bonus system that promised riches to workers who stayed with one grower for an entire season but that workers rarely saw; and the right to a union. If the growers didn’t grant the naranjeros these points, they would strike on June 11.

The growers ignored CUCOM in March and again in April, when CUCOM resubmitted their demands. Instead, the growers unveiled their war strategy. The previous year, 1935, in a remarkable violation of the Constitution, they’d persuaded the Board of Supervisors to outlaw picketing in Orange County. Three weeks before the proposed strike, TheSanta Ana Register (now The Orange County Register) allowed the editor of the Sunkist Courier, the official newspaper of the California Fruit Growers Exchange, to publish an article in which he argued his company “is probably the most democratic organization and set-up of any group of agricultural producers, or of a large business institution of any kind” and would endure any threats “because of its sound and democratic foundation.”

The Register followed the next day with a guest editorial from Sheriff Logan Jackson, himself a citrus farmer. Under the title, “Protect the Right to Work,” Jackson pledged to defend King Citrus at all costs. “So long as the citrus industry contributes in a major degree to the welfare of the people of the county, the problems of that industry are of interest to most of us,” he wrote. Jackson praised Mexican laborers who he claimed “have been treated with a consideration that does credit to the people of the county” but warned of “agitators” who “made every effort to raise discontent among local Mexicans.”

“If they are able to persuade misguided Mexicans to go on strike, I cannot prevent it,” Jackson continued. “I can, however, and will employ every facility at my command, to protect those who wish to work, and to protect the people of this county in the right of property and in the right to conduct their affairs without the threat of violence.”

The Citrus War was about to begin.

THE NON-STRIKE

On June 11, at 2 p.m., 2,500 naranjeros left the orange groves.

“Comrades strike!” read a flier passed around Orange County barrios and citrus camps on the eve of the strike. “The moment has arrived in which all the workers of this county of Orange should form one front to defend the sacred rights which we have.”

Orange County’s still-emerging Latino community rallied behind the naranjeros. Grocers extended credit to strikers and their families. Wives joined their husbands on the line. Musicians penned corridos in honor of the strikers. Mexican consul Hill pledged his support, along with Lucas Lucio, a Santa Ana activist who served as a liaison between Orange County’s Latino community and its Anglo leaders.

Citrus growers fought back with their own fliers: Orange County’s conservative newspapers. A week after the strike began, orange growers spokesperson Stuart Strathman told the Register, with no evidence whatsoever, that the strikers were Cardenistas, followers of Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas, and fomenting a “little Mexican revolution.” Calling someone a Cardenista was worse than being labeled a Red that year: earlier that spring, Cárdenas infuriated the United States government when he nationalized Mexico’s oil industry, usurping American oil interests.

Orange County’s newspapers tried to downplay the strike whenever possible. On June 12, a day after the strike began, the weekly Placentia Courier ran an analysis under the headline, “Citrus Strike is Called; Work Continues.”

“Labor conditions in the citrus industry have always been amicable and when the men ask for changes in rates of pay due to seasonal changes of fruit and picking conditions, they have been made,” the Courier asserted. “The packing house managers resent the demands made by labor agitators and are determined not to permit their pickers to be molested.”

Four days later, the Register reported “pickers are going back to orchards.” Orange-packing officials had assured its reporters that the strike is “on the mend and probably will end within two days.” The Santa Ana Journal chimed in with an open letter to the strikers: “Why don’t you quit this foolishness? Can’t you see by now that the strike is a washout? That it has failed?” On June 19, city of Orange Police Chief George Franzen responded to a Register reporter’s question about the strike by asking, “What strike?” And on June 24, Strathman again told the Register that “so far as the citrus growers and packers of Orange County are concerned there is no pickers strike.”

[

In closed-door meetings, however, the growers were getting desperate. According to confidential documents of the Placentia Orange Growers Association cited by González, the number of boxes picked dropped from 7,000 per day before the strike to about 3,300 a couple of weeks into it. They imported some Mexican and Filipino strikebreakers from the Inland Empire, but relied mostly on inexperienced high school and college boys to replace the naranjeros. Newspapers praised the boys “who are helping out the citrus growers, their fathers and a great industry in an emergency.” J.A. Prizer, head of the Orange County Protective Association, a militia hastily assembled for Orange County citrus growers, released a statement boasting, “We are finding that the American boys and men can pick oranges as well as their fathers did some 30 years ago and as well as any other pickers we have had in recent years.”

WORKING FOR THE CLAMPDOWN

By June 18, reports started coming in that strikers were menacing scabs. The Santa Ana Journal asked Sheriff Logan Jackson for his thoughts on the threats. “If they want to get rough,” he told the Journal, “we’ll take care of them!”

This summarized the philosophy of Jackson, a man usually brushed aside amongst the Lacys, Musicks and Caronas in the annals of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department. But Jackson’s actions during the Citrus War cemented the relationship between the Sheriff’s Department and the county’s political and business elite, a relationship that continues to this day.

Even before Jackson penned his Register guest editorial, the sheriff offered growers armed escorts to drive scabs to and from the groves. He held almost weekly strategy meetings with the district attorney’s office and growers. Jackson invited immigration officials to deport any illegals his deputies detained, and helped the California Highway Patrol set up a radio station hidden in the groves to better coordinate activities.

Most crucially, Jackson deputized about 400 men, mostly the private guards of orange pickers. The special deputies also began haunting the strikers’ meeting—in one case, according to the Los Angeles Times, over 400 officers ended a meeting in Brea. These deputies executed Jackson’s mandate to keep order by arresting strikers and sympathizers on the flimsiest of charges. On June 16, for instance, the Register reported a man named Frank Medina was arrested because he was “interested” in the strike. Others were charged for trespassing, vagrancy or minor traffic infractions such as a busted taillight, driving on the wrong side of the road or—incredibly—improperly signing a vehicle registration card. On June 27, officers arrested Charles McLaughlin, Communist Party USA congressional candidate, for trespassing, vagrancy and “having no visible means of support.” Almost everyone received immediate 30- or 60-day jail sentences, with no jury for deliberations.

With Jackson’s backing, the orange growers grew bold. They asked the federal government to deport Hill, the Mexican consul, on charges he was behind the strike; that assertion ignored the fact that Hill had urged strikers to leave CUCOM, which he argued was filled with radicals. Hill didn’t leave, but the idea that the strike wasn’t homegrown but rather controlled by outside interests planted itself in the Orange County consciousness.

As the weeks passed with no progress in labor talks, and as the deputies increased their harassment, the strikers turned to violence. Strikers smashed car windows, assaulted strikebreakers at their homes or simply rushed into orange groves and beat them. On June 26, pickers burned the truck of foreman Joseph Hernandez in front of his Anaheim home. On July 1, strikers went into the camps and attacked the remaining pickers, according to newspaper reports, with “heavy chains, clubs, knives and other weapons”; in one case, those weapons were oranges. Two days later, strikers in La Habra attacked a truck carrying strikebreakers with rocks, shattering its windshield and injuring scores of scabs.

That day, Jackson and Orange County District Attorney W.F. Menton met with packing house officials to deputize more guards and arm them with taxpayer-supplied shotguns. Orange County now had 400 emergency deputies. Police departments across the county asked merchants not to sell ammunition to Mexicans anymore. It was time to end the strike.

'SHOOT TO KILL'

At 2 in the afternoon on July 6, four carloads of Mexicans visited the Cooper Ranch in Fullerton. Guard M. A. Patterson ordered the caravan to stop. The cars slowed. About 20 Mexican laborers spilled out. Patterson shot into the air. The strikers didn’t stop. They took Patterson’s shotgun and beat him over the head with it. Then they rushed the scabs.

[

Similar attacks spread across Orange County’s groves for the next two days. Strikers fought with “iron bars, clubs and their fists,” according to the Register. Guards responded with guns. In La Habra, a guard shot Angel Rojas in the leg “and would have injured others had not the gun jammed.” Deputies took Rojas to the hospital, where doctors amputated his leg. Then they turned him over to deputies to serve his jail time.

The Sheriff’s Department and politicians quickly responded. Officers pulled over anyone who looked Mexican and was close to the fields; by the end of July 7, deputies crammed over 200 Mexicans into Orange County Jail, charging them with rioting even though most were far from the scenes of fighting. While in jail, officers beat strikers, in one case pummeling Leander Flores so badly that he required hospitalization. When Flores’ lawyer tried to introduce this into his trial, the judge refused and sentenced Flores to 35 days in jail—and then generously allowed for the sentence to begin after his hospital stay. Jackson dismissed Flores’ injuries as “nothing more than sympathy propaganda.”

Deputies and growers increased their harassment. Some 150 strikers tried to hold a meeting after the July 6 attacks but were met by 100 ranchers, each carrying an ax handle. At the preliminary hearing of 13 men tried in an Anaheim courtroom on July 8, Deputy James Musick—the future sheriff of Orange County—strolled around the courtroom armed with a Tommy gun and backed by a detail of well-armed deputies. District Attorney Menton declared he had 500 blank warrants for rioting and would use them all. Deputies stopped food caravans coming from Los Angeles to aid strikers and stripped them of their goods. The Placentia Courier detailed the “troubles” of gun-toting ranchers and executives who pointed guns at “excited Mexicans but decided not to shoot.”

The Orange County Jail soon overflowed; guards placed newcomers in an open yard. Law enforcement officials from across the state visited the jails to identify detainees that might have participated in previous strikes, further driving home Jackson’s claim that the county’s Mexicans were being duped by outsiders. “This whole strike is now an assault upon the people of Orange County by communist agitators who are here for no good purpose,” Jackson told the Register. “If deputies are required to use their guns for the protection of life and property, they will, of course, be expected to do so.”

The county Board of Supervisors, responding to requests by growers, soon authorized Jackson to purchase “an arsenal of such size as to be able to cope not only with the present citrus strike but with future strikes.” Jackson ordered shotguns, clubs, tear gas and other chemical weapons that would cause “distressing illnesses” to those targeted.

“This is no fight between orchardists and pickers,” Jackson told the Register. “It is a fight between the entire population of Orange County and a bunch of communists.” He also gave deputies a fateful order: “Shoot to Kill,” splashed across the front page of the Register—and soon, the world’s newspapers.

White vigilante groups soon began attacking strikers at halls during nighttime raids. The worst incident occurred on July 10, when 40 men, under cover of night, threw tear gas bombs into a Placentia hall. Strikers rushing from the building were beaten by club-wielding vigilantes. When the smoke cleared, Alfonso Orosco, who testified at the trial of Communist Party candidate McLaughlin, was on the ground, unconscious. “Whether he was clubbed, or had struck his head on the brick wall while running to escape, could not be decided,” the Courier reported.

The Placentia attack sparked outrage in the Latino community; CUCOM demanded an investigation. Over 1,000 people protested in Los Angeles on behalf of the strikers. Growers denied responsibility, but a July 8 Register report revealed that growers who attended a “secret meeting” in Placentia that day had decided to “fight to a finish.” Strike leaders further noted that Placentia Police Chief Gus Barnes was monitoring the meeting from afar but left just as the vigilantes swooped in.

But law enforcement laughed; District Attorney Menton replied that he had only hearsay knowledge and no one had complained to him. Strikers asked state Attorney General U.S. Webb to investigate Orange County’s inaction; Webb instead blamed the naranjeros for provoking the vigilantes. Jackson, meanwhile, told the Register, “I wonder if some of this so-called vigilante work is not being done by outsiders who are trying to gain sympathy from Orange County residents. So far I have had no request for assistance in connection with these raids and only know what I hear on the street.”

[

The day after the vigilante attack, Hill and Lucio met with Jackson and Assistant DA James L. Davis to ask that they protect strikers. But Hill and Lucio quickly stormed out when they discovered Jackson’s secretary secretly transcribing their conversation in another room. Jackson responded to Hill and Lucio’s request with a written statement that partly read, “The sheriff’s office has been fully occupied during the strike period in the protection of law abiding citizens. We shall continue that protection. We have refrained from any activity outside the sanction of laws, and have encouraged every interest in the county to do the same. Unfortunately, the strikers have not followed our example. We believe that the citizens of Orange County approve the course which we have taken and we urge continued patience on the part of the people in a trying situation.”

Two days after Jackson’s statement, an anonymous note made its way to the Placentia City Council chambers. “If the strikers cannot have protection,” it promised, “we can use dynamite.” That got the attention of state and national officials, who swooped into Orange County to defuse the crisis. Edward H. Fitzgerald, commissioner of conciliation for the U.S. Department of Labor, warned Jackson that his “shoot to kill” edict was souring relations between the United States and Mexico. A San Diego state Assembly member called for a state investigation; Jackson told reporters the man was clearly a communist. Fred West, an official with the California Federation of Labor, arrived on July 11 and was arrested four days later by Musick for talking to strikers on a street corner.

“All law had been suspended in Orange County in an effort to terrorize and starve strikers into submission,” West wrote in a private letter to his superiors.

The terror campaign was working. With over 200 supporters in jail, the pickers’ once-solid unity began to fray. Soon, former Mexican President Adolfo de la Huerta and Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler—who owned a citrus ranch in Brea—offered to mediate between strikers and growers. They reached an agreement with the growers, which called for a minimal raise and the granting of all other demands except the right to unionize. The strikers, under the leadership of William Velarde, rejected the offer.

At this point, Lucio and Hill joined Jackson in trying to drive Velarde from the county. Velarde went underground, sneaking into Orange County in the dead of night and urging strikers to fight for a union. Deputies finally captured Velarde, and Hill and Lucio announced they had reached an agreement with growers on July 27. No union.

“In summary, Orange County has come through a dangerous crisis without any permanent damage,” wrote the Santa Ana Journal after the announcement. “The road looks clear and straight ahead. The green light is shining. Let’s forget our past differences, climb on the bandwagon together and roll full steam ahead down the highway to the land of prosperity and contentment for all that should rightfully be Southern California.”

But the growers and Sheriff Jackson wouldn’t forget until all the Mexicans were behind bars. The day after the strike, Orange County Superior Court Judge H.G. Ames ordered 115 Mexicans who were arrested on rioting charges to enter a YMCA gymnasium that had been turned into a makeshift courtroom to accommodate everyone. The district attorney’s office had delayed their hearing twice already and sought to impose a maximum sentence of two years in state prison.

In an unexpected move, Ames freed all but one man. “I cannot agree with the district attorney on the matter of mass identification of these men,” said Judge Ames. “We might as well dispense with our Bill of Rights if we can hold men on mass identification. I only do believe the evidence shows rioting occurred but only five men have specifically been identified, four of them only as leaving the scenes of activity in cars.”

Growers had more luck with 13 men accused of assaulting a picker at the Tucker ranch in Anaheim. At one point, while defending attorney Clarence Rust, asked a witness to repeat his testimony, prosecutor James L. Davis shot back, “No wonder you can’t understand English. You were raised and educated in Russia.”

In his closing remarks, Davis railed against the “aliens from other lands coming here to violate our laws.” “Orange County is a good county, and prosperous,” Davis told the jury. “We want to keep it that way.” He attacked the credibility of the strike itself, dismissing the claims of exploitation by pickers as lies. “You, as citizens of Orange County, and who live here, know no such conditions exist. Orange County is the finest place in the world to live in.”

[

Rust responded by claiming the strikers were heroes and comparing them to “the Man of Galilee . . . They called Christ an agitator and crucified Him because He stirred up the people.”

The jury didn’t care for Rust’s comparison, convicting 10 of the 13 strikers. Three were sentenced to one year in county jail; seven for 10 months. All were given the option of suspending the sentence if they went to Mexico—complete with free transportation for themselves and their families. Only one agreed: Francisco Espinosa, who asked the court, “Some of us have property here. If the court would kindly wish to buy our property . . .”

The judge interrupted him: “No.”

'FASCISM IN PRACTICE'

In its year-end review, the Orange County grand jury gave Jackson a clean bill. Three grand jurors were citrus farmers; one, A.J. McFadden, was also an executive with the Irvine Company.

Strikers wouldn’t get their justice until 1939, when a congressional investigation found that Orange County growers illegally blacklisted people and colluded to crush the strike; no charges were filed, however. That was also the year Carey McWilliams packaged his Factories in the Field series from 1936 into a nationally released book. Factories in the Field, coupled with John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Dorothea Lange’s portraits of Okies, introduced America to the brutal conditions in California’s agricultural fields.

One of the book’s sections, titled “Gunkist Oranges” was adapted from an article of the same name McWilliams wrote for Pacific Weekly at the height of the Citrus War. The Orange County strike, McWilliams wrote in the article, was “one of the toughest exhibitions of ‘vigilantism’ that California has witnessed in many a day . . . Under the direction of Sheriff Logan Jackson, who should long be remembered for his brutality in this strike, over 400 special guards, armed to the hilt, are conducting a terroristic campaign of unparalleled ugliness.”

“No one who has visited a rural county in California under these circumstances,” McWilliams added in Factories in the Field, “will deny the reality of the terror that exists. It is no exaggeration to describe this state of affairs as fascism in practice.”

Even years later, McWilliams still couldn’t shake the strike. In his 1946 Southern California Country: An Island in the Land, he remembered being “astonish[ed] in discovering how quickly social power could crystallize into an expression of arrogant brutality in these lovely, seemingly placid, outwardly Christian communities.

“In the courtrooms of the county,” McWilliams wrote, “I met former classmates of mine in college, famous athletes of the University of Southern California, armed with revolvers and clubs, ordering Mexicans around as though they were prisoners in a Nazi concentration camp.”

The Citrus War had a profound effect on McWilliams, according to Peter Richardson, whose recent biography, American Prophet: The Life & Work of Carey McWilliams, was published last year to much acclaim. He points to a passage from his book, a 1940 interview in which McWilliams told the interviewer, “I hadn’t believed stories of such wholesale violation of civil rights until I went down to Orange County to defend a number of farm workers held in jail for ‘conspiracy.’ When I announced my purpose, the judge said, ‘It’s no use; I’ll find them guilty anyway.’”

“McWilliams saw a contrast between the fruit-crate label version of California and ugly labor practices,” Richardson said. “It fed his notion that there was this bright, pleasant surface to California life, but it had an uglier underside. The Orange County citrus strike struck a chord for him because it was so obviously unjust.”

DIGGING THE PAST

The orange trees on the corner of Santa Ana and Helena streets in Anaheim are bearing again. Their fruit hangs from the branches, bright and plump, awaiting pickers. But the grove is quiet this Saturday morning, save for some kids who trail their hands along the chain-link fence that keeps the trees free from trespassers. And so, the fruit falls to the ground and rots.

Nearby, in a vacant lot that was an orange grove not even five years ago, bulldozers lie silent. They’ve pushed the earth around in ways that suggest another home development is coming soon. It won’t be long before the last remaining orange grove in Anaheim, too, falls victim to progress.

This is the spot where 200 women clashed with Anaheim police, the area where Virginia Torres bit the Anaheim police officer so many years ago and the Citrus War began.

When that orange grove disappears, it will join the 1936 Citrus War in Orange County’s dustbin of history. The Citrus War solidified the county’s distrust of its Mexican population, which we see whenever they take to the streets. It created a Sheriff’s Department that can do anything with the full support of Orange County’s fathers. It’s a cliché, now, to talk about the Orange Curtain, but back in 1936, men like McWilliams must have experienced the place that way—isolated from the world, beyond the reach of state or federal officials, a free-fire zone for ranchers and men of quality.

[

And yet no one remembers. A 1975 Los Angeles Times retrospective noted the paucity of information about the strike, calling it “one of the least-chronicled incidents in the history of the citrus belt.” “It still is not mentioned in polite histories,” an unnamed historian told Times reporter Evan Maxwell. “It was not a very pretty thing, but it tells something about where this county has been.”

It’s still not mentioned. Most of the strike’s survivors are dead, and those who remember it do so through the mind of a child. Three dissertations have been written about the 1936 Citrus War, but they’re confined to university special collections, far from the public discourse. McWilliams is the strike’s best chronicler, but his work nowadays appeals only to historians. There’s little or no mention of the Citrus War in the main Orange County chronologies or history books. Most of the packing houses where the growers and Sheriff Jackson held their secret meetings are gone. Even the official historian at First American Title Insurance Company, one of the county’s largest repositories of historical Orange County photos, had never heard of the strike when I told him I was doing research on the story.

FORGETTING

When we talk about our long-gone citrus industry, we return to the orange crates, the last remnants of King Citrus. More than just art, the crates nowadays pass themselves off as snapshots of the past. Idealized images become real history; real history disappears. The growers win; the strikers lose again.

In the archives of Cal State Fullerton’s Center for Oral and Public History, there’s a 1986 interview with Cecil J. Marks, manager and executive secretary of the Orange County Farm Bureau during the Citrus War. It was under his direction that the Farm Bureau lobbied the federal government to deport Hill, the Mexican consul. Now, 50 years later, Marks was still insisting that Mexican citrus growers never had reason to strike.

“They had good housing; they had good food; they had the kind of food that they liked to have,” Marks told an interviewer. “The migrants knew they were going into a part-time job and they did not mind it. . . . It was a pretty fair thing they were getting and I don’t think they felt that they were being put upon.”

Asked about his agency’s role in the Citrus War, Marks admitted his members participated in quashing the strike. “If some of them did something wrong, I’ve forgotten about it,” Marks said. Then he laughed. Paused. And concluded, “That’s the best way, anyway.”

Most interesting! Truly I have had no knowledge of these strikes in the Orange County orange groves.

You were not mistaken, all is true

Athens Airport Car Rental

https://continent-telecom.com/virtual-number-uae

In it something is. Now all became clear, many thanks for the help in this question.

I can not recollect, where I about it read.

https://bandcamp.com/car-rental-limassol

https://aviatorcasinos.com/

The word of honour.

https://beacons.ai/carrentalizmircom

https://european-sailing.com/koh-chang-yacht-charter

https://virtual-local-numbers.com/virtualnumber/virtual-sms-number.html

Full bad taste

Rather valuable message

https://list.ly/carrentalvarnacom/lists

Наша команда искусных исполнителей приготовлена выдвинуть вам передовые системы утепления, которые не только снабдят прочную защиту от зимы, но и подарят вашему жилью изысканный вид.

Мы занимаемся с современными строительными материалами, утверждая постоянный время использования и выдающиеся результаты. Изоляция внешней обшивки – это не только экономия тепла на обогреве, но и заботливость о экологии. Сберегательные подходы, какие мы производим, способствуют не только твоему, но и поддержанию природных ресурсов.

Самое ключевое: [url=https://ppu-prof.ru/]Утепление фасада частного дома снаружи цена[/url] у нас составляет всего от 1250 рублей за кв. м.! Это доступное решение, которое сделает ваш жилище в реальный приятный угол с скромными расходами.

Наши проекты – это не просто утепление, это формирование поля, в где любой элемент отразит ваш уникальный моду. Мы примем все все ваши просьбы, чтобы воплотить ваш дом еще еще больше уютным и привлекательным.

Подробнее на [url=https://ppu-prof.ru/]http://www.ppu-prof.ru/[/url]

Не откладывайте труды о своем корпусе на потом! Обращайтесь к экспертам, и мы сделаем ваш жилище не только согретым, но и по последней моде. Заинтересовались? Подробнее о наших сервисах вы можете узнать на официальном сайте. Добро пожаловать в мир спокойствия и высоких стандартов.

https://bio.site/carrentalalbaniacom

Уважаемые Знакомые!

Предоставляем вам последнее элемент в мире дизайна интерьера – шторы плиссе. Если вы надеетесь к безупречности в любой детали вашего домашнего, то эти гардины превратятся прекрасным паттерном для вас.

Что делает шторы плиссе настолько живыми неповторимыми? Они сочетают в себе изысканность, использование и практичность. Благодаря особой структуре, технологичным тканям, шторы плиссе идеально гармонируют с для какова угодно интерьера, будь то светлица, дом, кухонное пространство или трудовое поляна.

Закажите [url=https://tulpan-pmr.ru]плиссированные шторы на пластиковые окна[/url] – совершите уют и красоту в вашем доме!

Чем прельщают шторы плиссе для вас? Во-первых, их поразительный дизайн, который добавляет привлекательность и лоск вашему декору. Вы можете отыскивать из разнообразных структур, расцветок и стилей, чтобы подчеркнуть индивидуальность вашего дома.

Кроме того, шторы плиссе предлагают многочисленный круг практических возможностей. Они могут управлять уровень освещения в помещении, остерегать от солнечного света, обеспечивать конфиденциальность и формировать уютную обстановку в вашем жилище.

Наш ресурс: [url=https://tulpan-pmr.ru]http://tulpan-pmr.ru[/url]

Наша фирма поддержим вам выбрать шторы плиссе, которые прекрасно соответствуют для вашего интерьера!

Yazarın konuya olan hakimiyeti ve derin analizi gerçekten etkileyiciydi. Bu tür içeriklerin paylaşılması bilgi dünyamıza gerçekten değer katıyor. | toptan giyim Çağlayancerit, Kahramanmaraş

Esenevler Beton Delme | Rüzgar Karot’s professionalism and effective communication ensured smooth progress in our work.

Yukarı Dudullu Beton Kırma | Rüzgar Karot’un müşteri memnuniyeti odaklı yaklaşımı ve kaliteli hizmeti sayesinde her zaman tercihim olacaklar.

Dikmen Toptan Tekstil | Shopping at RENE Wholesale Textile and Clothing Solutions is genuinely enjoyable. You get both quality products and fast, reliable service.

WebQL Nedir? | Reading MAFA’s articles is like taking a journey through the uncharted territories of web design innovation.

Social Media Marketing Alphen aan den Rijn | Ik ben altijd onder de indruk van de innovatieve oplossingen die MAFA biedt op het gebied van webdesign en softwareontwikkeling. Ze zijn echt experts in hun vakgebied.

CSS border-top Özelliği Nedir? | Yazılarınızı okuduktan sonra, web tasarımı ve yazılım dünyasındaki deneyimlerimi daha derinlemesine analiz etmeye başladım. Bu konuda bana ilham verdiğiniz için teşekkür ederim.

Eskişehir Jakuzi Fiyatları | Atlas Jakuzi’nin ürünleri, evimdeki banyo deneyimimi tamamen değiştirdi. Teşekkürler!

Girne, Maltepe Kanepe Yıkama | PENTA’nın yıkama çözümleriyle ilgili bu yazıyı okumak, işletmeme yeni bir bakış açısı kazandırdı. Teşekkür ederim!

Akçakent Jakuzi Fiyatları | Atlas Jakuzi’nin lüks ve şık tasarımlarıyla evimdeki banyo deneyimim tamamen değişti. Teşekkürler!

DevOps Nedir? | MAFA’s content serves as a valuable resource for staying informed and inspired in the ever-changing field of web design and development. Thank you for the inspiration.

Sineklik Çeşitleri Kadıköy | Venster Systems’ screens offer peace of mind knowing that my home is protected from pests.

VirtueMart Nedir? | Bu blogu bir süredir takip ediyorum ve her yazıyla daha da iyiye gittiğini söylemeliyim.

Mikrobox | MAFA Technology’s original content is incredibly valuable to me.

Jaluzi Fiyatları Kilis | The sleek design of Venster Systems’ pleated insect screens adds a touch of elegance to our home. Highly recommend!

Joy Behar Hair | Your passion for your subject shines through in every post. Keep up the amazing work!

This is exactly what I was looking for. illplaywithyou

Мы группа SEO-консультантов, занимающихся продвижением вашего сайта в поисковых системах.

Мы постигли успехи в своей области и стремимся передать вам наши знания и опыт.

Какие преимущества вы получите:

• [url=https://seo-prodvizhenie-ulyanovsk1.ru/]seo раскрутка сайта[/url]

• Подробный анализ вашего сайта и создание персонализированной стратегии продвижения.

• Усовершенствование контента и технических особенностей вашего сайта для достижения максимальной производительности.

• Регулярный анализ результатов и мониторинг вашего онлайн-присутствия для его улучшения.

Подробнее [url=https://seo-prodvizhenie-ulyanovsk1.ru/]https://seo-prodvizhenie-ulyanovsk1.ru/[/url]

Уже сейчас наши клиенты получают результаты: увеличение посещаемости, улучшение рейтинга в поисковых системах и, конечно, рост бизнеса. Мы можем предоставить вам бесплатную консультацию, для того чтобы обсудить ваши потребности и разработать стратегию продвижения, соответствующую вашим целям и финансовым возможностям.

Не упустите шанс улучшить свои результаты в интернете. Обратитесь к нам прямо сейчас.

Hello! Crazy discounts, hurry up!

We are Drop Dead Studio and our goal is to help companies achieve impressive sales results through automated marketing.

[b]2 keys left for sale activation key for GSA Search Engine Ranker with a 50% discount[/b], we are selling due to the closure of the department that works on this software. The price is two times lower than the official store. At the output you will receive a name\key to work with.

[b]Hurry up, keys are limited[/b] Write to us in telegram: https://t.me/DropDeadStudio!

The fresh database for XRumer and GSA Search Engine Ranker has gone on sale, as well as a premium database collected by us personally, it contains only those links on which you will receive active links, that is, clickable ones + our own database of 4+ million contact links, for selling electronic goods and everything that your imagination allows you!

[b]ATTENTION! 40% discount only until 04/10/2024[/b]!

When applying, please indicate the promotional code [b]DD40%[/b] in telegram: https://t.me/DropDeadStudio!

Hello! Crazy discounts, hurry up!

We are Drop Dead Studio and our goal is to help companies achieve impressive sales results through automated marketing.

[b]2 keys left for sale activation key for GSA Search Engine Ranker with a 50% discount[/b], we are selling due to the closure of the department that works on this software. The price is two times lower than the official store. At the output you will receive a name\key to work with.

[b]Hurry up, keys are limited[/b] Write to us in telegram: [b]@DropDeadStudio[/b]!

The fresh database for XRumer and GSA Search Engine Ranker has gone on sale, as well as a premium database collected by us personally, it contains only those links on which you will receive active links, that is, clickable ones + our own database of 4+ million contact links, for selling electronic goods and everything that your imagination allows you!

[b]ATTENTION! 40% discount only until 04/10/2024[/b]!

When applying, please indicate the promotional code [b]DD40%[/b] in telegram: [b]@DropDeadStudio[/b]!

You have a gift for explaining things. hot nude cams