Cameron King was lost.

He was driving his mother Sonia’s pearl Cadillac Escalade around a Memphis, Tennessee, parking lot, with Sonia riding shotgun. They were on their way home from the Cheesecake Factory, where they’d eaten with Cameron’s Aunt Carrie and his sisters Kaelah and Crista-Lynn. It was the final night of Cameron’s trip home to Memphis. In the morning, he’d fly back to California, where he’d moved six months earlier.

But Cameron had a horrible sense of direction, even on familiar roads. He rambled the car down one wrong turn after another while Sonia laughed. The detours didn’t bother her. This was one of the happiest nights she’d spent with her 21-year-old son. As they drove, Cameron charmed his mother with his soft, Southern twang, holding her hand, telling her he loved her and thanking her for being his mom. What made Sonia happiest was that her son had been sober for six months.

“I had never felt more joy than that night in my heart,” Sonia says.

Up to then, Cameron had led a tumultuous life. His father was a union ironworker who sold meth on the side. He was an addict, too. Sonia left Cameron’s father when Cameron was young; she raised her son with the help of her sister Carrie and her parents.

Sonia made a joyous life for him. As a boy, Cameron was happy and active. He was a Boy Scout and a football player, and he easily made friends. He was funny and charming, with a sideways smile. But being raised without a father left Cameron feeling different.

As do most teenagers, Cameron began smoking weed and drinking at parties. Before long, prescription opiates and amphetamines crept into Cameron’s friend group. At the time, from 2014 to 2016, Tennessee had the third highest opioid-prescribing rates in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

When Cameron was 18, his best friend Kyle Blevins died of an overdose. Cameron was shook, but he didn’t sober up.

A year later, another friend, Mark, overdosed in the passenger seat of Cameron’s truck while Cameron was driving. Cameron panicked, swerved and rolled his truck five times. Mark was ejected from the car and lay lifelessly beside the road. Paramedics revived Mark with naloxone, the opiate-overdose reversal drug, and the pair narrowly escaped tragedy.

“I was so scared,” Sonia says. “I knew in my heart that he was with the same crowd of people and that this could happen to him at some point.”

Cameron unsuccessfully began trying to get sober, first in Tennessee, then in New Orleans. By the time he reached California in August 2018, he seemed ready for sobriety. After completing a 30-day in-patient program in San Diego, Cameron came to San Clemente for sober living. He excelled in the program. He committed himself to attending AA meetings, helping his housemates in sober living, and got a job at the Dana Point Best Western.

“Such a sweet kid. He was always being of service to the guys in the house,” says John C., Cameron’s AA sponsor.

“I owe a lot to him,” says Eric, Cameron’s sober-living roommate. “He really got me out of my shell.”

On Jan. 24, 2018, the morning after his car ride and trip to the Cheesecake Factory with his mother, Cameron left Tennessee and returned to San Clemente. He promised to remain sober and to Facetime his youngest sister, Crista-Lynn, for her birthday on April 14. But that call never came.

Cameron died of a heroin overdose on April 8, 2018.

* * * * *

Stories such as Cameron’s are tragically familiar in Orange County, where there have been 4,480 overdose deaths since 1999. Compared to similar-sized counties in California, only San Diego County experiences more overdose deaths per 100,000 residents, stated Dr. Nichole Quick, deputy health officer for the OC Health Care Agency. Parts of Seal Beach, Huntington Beach and San Clemente, as well as neighborhoods off Beach Boulevard’s Motel Row, experience death rates far above county and state averages.

Laws restricting opioid prescriptions—aimed at stopping the problem where it often begins, in doctors’ offices—have been unsuccessful. OC saw a 15 percent decrease in opioid prescriptions since 2015, yet overdose-death rates and emergency-room visits continued climbing. While prescription-overdose rates declined in the past 12 months, synthetic-opioid overdoses, namely from fentanyl and its minimally altered analogues, have climbed drastically.

Professors, public-health experts and criminologists agree the problem is worsening. Drugs tainted with fentanyl and easily accessible drugs will reportedly make 2018 the deadliest year for drug overdoses in OC.

* * * * *

You’ve probably heard news reports refer to fentanyl as “China White,” however that hasn’t always been the case. Through the 1970s and ’80s, China White referred to highly refined, highly potent white heroin produced in the so-called “Golden Triangle,” a mountainous area along the borders of Myanmar, Thailand and Laos. The drug was prevalent in OC back then, so much so that a Huntington Beach hardcore punk band named themselves after the drug. Even then, however, dealers sold fentanyl analogues as China White to unsuspecting buyers.

Globally, the first two reported deaths from a fentanyl analogue sold as China White occurred in Orange County in 1979, Politico’s Jack Shafer wrote in 1985. The drug was alpha-Methylfentanyl, similar to pharmaceutical fentanyl, but less potent and with longer lasting effects. Police had never seen the drug, and it took years to determine what it was and why it was so lethal.

That trend continues today, as unidentified fentanyl analogues kill more people every year.

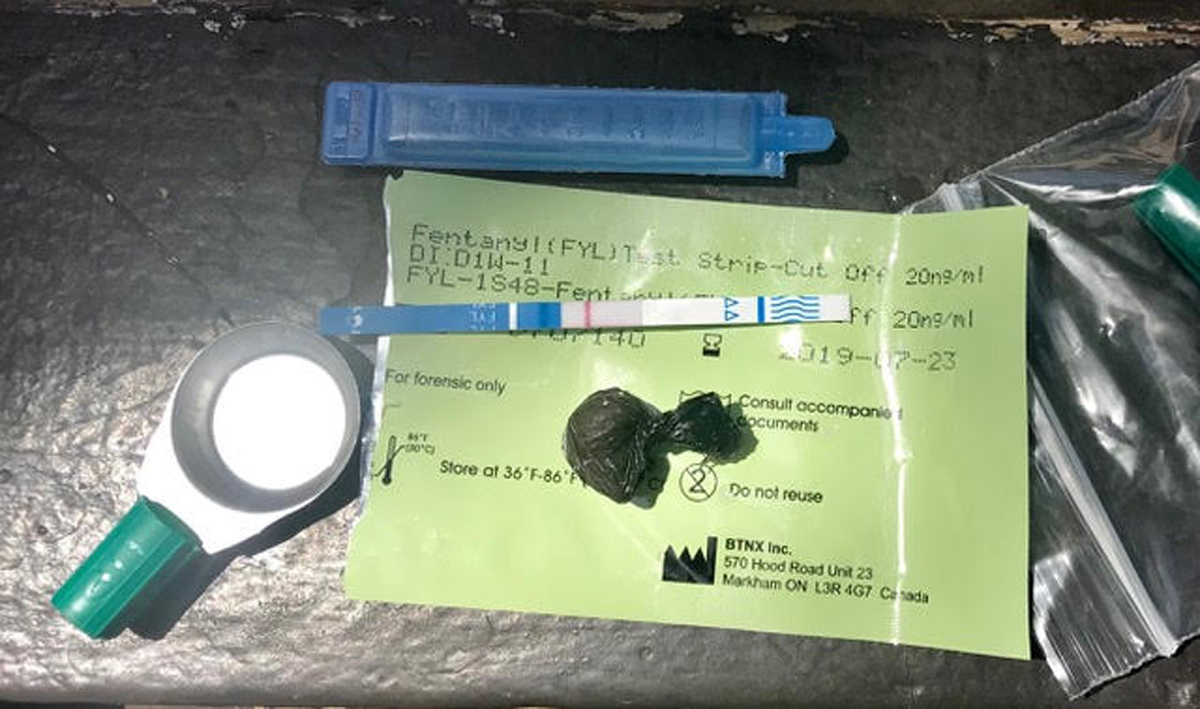

Aimee Dunkle founded Solace Foundation in 2015 after her son Ben died of a heroin overdose. She distributes free boxes of the opioid-reversal drug naloxone to people likely to witness an overdose and teaches people how to successfully save lives with it. In 2017 alone, Solace Foundation reversed 1,085 overdoses with naloxone. Dunkle also tests drugs for fentanyl contamination, and says contamination is increasing at alarming rates.

“Back in 2016, it was very specific that we had black tar [heroin]; you didn’t hear about China White,” Dunkle says. “Suddenly, at the end of 2017, you hear all about China White.” Dunkle estimates 95 percent of heroin in OC contains a fentanyl analogue.

Fentanyl contamination isn’t confined to heroin. It’s been found in everything from street-pressed Xanax and oxycodone to cocaine and methamphetamine. Dunkle began hearing about fentanyl contamination in 2017 after a Costa Mesa man was revived by naloxone after overdosing on cocaine. The cocaine must’ve been contaminated with fentanyl or another opiate because naloxone only reverses opioid overdoses. She began testing methamphetamine for fentanyl that summer, after a longtime meth user reported strange effects to Dunkle.

“I’ve been using meth for 20 years up in Los Angeles,” he told Dunkle. “I’ve been in OC for six weeks, and every time I use the meth here, I fall asleep. What’s with that?” Dunkle tested the man’s bag and found it positive for fentanyl.

“Back in the day, there was pure meth,” says Tom Buckley, CEO of the drug-treatment facility Pacific Solstice. Those days are gone. Users of contaminated meth unintentionally find themselves physically hooked on opiates.

But why would dealers cut their supply with fentanyl? When you consider the possibility of facing drug-induced homicide charges for selling a tainted bag alongside fentanyl’s lethality—medicinal doses of intravenous heroin (diamorphine) range from 10 milligrams to 100 milligrams, while intravenous fentanyl ranges from 0.05 milligrams to 0.1 milligrans—cutting your supply with a deadlier drug doesn’t make sense. And cutting a stimulant such as methamphetamine with a depressant makes even less sense, especially from a marketing perspective.

Both answers can be found by examining narcotics suppliers.

Fentanyl’s cheap cost of production—which doesn’t require laboring in poppy fields—as well as its laboratory-guaranteed potency, means that a miniscule amount can strengthen weak heroin. Also, because a kilo of fentanyl goes further than a kilo of heroin, much smaller quantities can be smuggled.

A 2017 DEA report supports this. Mexican black tar heroin, the most prevalent variety in California in 2015, was purest in San Diego (averaging 33.7 percent) and cheapest (37 cents per pure milligram). As it climbs the coast, purity decreases and cost rises. Los Angeles black tar averaged 21.6 percent purity at 80 cents per pure milligram, while San Francisco tar averaged 9 percent purity at $1.35 per pure milligram. Because distributors in each metropolitan region cut purity and raise prices, it’s likely they could spike low-quality heroin with fentanyl to appease customers. Although San Diego was the only California city found to have fentanyl-tainted heroin in 2015, the report occured before the recent uptick of fentanyl deaths.

Fentanyl contamination in cocaine and methamphetamine isn’t as common as it is in street-pressed Xanax, according to regular users. However, lacing stimulants with opioids would strengthen the drug’s rush through a speedball effect. Methamphetamine and cocaine aren’t physically addictive. Adding physically addictive drugs such as fentanyl would make quitting more painful for a dealer’s customer base.

“This will reverberate for the next decade or longer,” Buckley says. “The drug supply is tainted, and the amount of fentanyl that’s out there . . . We’ve just scratched the surface. Our kids’ kids are going to be affected by this.”

* * * * *

Access to drugs online is as disturbing as contamination. Heroin, fentanyl, methamphetamine, Xanax, LSD, even DMT are easily found on OC Craigslist, if you know how to look. On a recent afternoon, simply by logging onto OC Craigslist, I found 13 dealers selling heroin, 25 selling methamphetamine, seven selling Xanax and four offering fentanyl. Drugs are advertised under nicknames such as “roofing tar” for heroin, “two-foot ladders” for Xanax, and “Chinese tiles” for fentanyl. Wondering why there’s so much Tina Turner memorabilia and concert tickets on Craigslist, even though ALL her upcoming shows are in Europe? Because that’s how you sell meth on Craigslist. And dealers offer their locations, phone numbers and names in these posts. Dealers avoid arrest by quickly removing posts and changing locations and phone numbers. Selling drugs online isn’t new, but fentanyl’s market dominance is.

Cal State Fullerton professor Jonathan Taylor and UCLA Ph.D. student Heather Agnew track the global drug market. Both agree that a majority of America’s fentanyl is manufactured in China or a nearby country such as India. Both countries export vast quantities of chemicals, making smuggling fentanyl or its precursors to Mexico and America easy.

“A lot of [fentanyl is] being shipped to businesses that do a lot of transnational commerce. A huge hub for this kind of trafficking is in San Bernardino,” Agnew says. Industrial manufacturing companies already purchase large quantities of chemicals from China. Therefore, shipping unmarked bags of white powder to these regions would elude suspicion. Coincidentally, most Craigslist dealers I saw selling cheap bulk quantities of fentanyl were in the Inland Empire.

Although Taylor hopes China’s recent ban on fentanyl manufacturing will be successful, he believes chemists with strong connections to American or Mexican buyers could continue producing fentanyl without faltering. Chemists and potential drug traffickers often meet on dark websites such as Wall Street Market and Dream Market. If the partnership works, chemists and traffickers will conduct business directly, without middleman websites such as Dream Market. Access to fentanyl remains unfettered for these chemists and traffickers, even though Dream Market banned fentanyl in May 2018, Taylor says.

Online purchasing may affect those most vulnerable: people in treatment. Because many rehab clients aren’t from OC and lack connections, Craigslist is often the first place they go to buy drugs after relapsing. A former rehab counselor, who agreed to speak anonymously, said he first heard about clients buying drugs off Craigslist in 2014, immediately after he began counseling.

“It seems to me that people who’ve bought off Craigslist don’t have any fear of it being an undercover cop. It doesn’t concern them that it’s a sting,” he said. Six months ago, three clients of his died in one week after responding to the same Craigslist ad, which was selling fentanyl-contaminated heroin.

For Cameron, online access to contaminated drugs proved fatal.

* * * * *

After returning from Tennessee in January 2018, Cameron left treatment. A friend from meetings said he could sleep in the cabin of his boat in Dana Point Harbor for $600 per month. That was too expensive for Cameron alone, so he asked his best friend Jack to move in. Cameron would sleep in the main cabin, and Jack would take the couch. It seemed the perfect arrangement: Both were committed to sobriety and seemed to have promising futures.

But for Jack’s father, John, who’d been sober for 18 years, it was troubling news. When Jack told John about the boat, John turned to his wife and said, “That’s trouble. Both these kids are going to go out.”

The relapse came in early March, about two months after Jack moved onboard. Jack had noticed Cameron acting strange, and then, one afternoon, Cameron greeted Jack with a pair of Four Lokos, caffeinated alcoholic beverages. The party was on. Soon after, the boys were drinking and smoking a little weed regularly.

“I was okay with just that,” Jack recalls. “But I could see Cameron wanted more.”

The boys met a cocaine connection at a Dana Point Circle K. A week later, they met the same connection at a Chevron off Camino Real in San Clemente, but this time, he had something different.

“The guy said his coke was shitty but he’s got this,” Jack recalls Cameron saying as he showed his friend a gram of heroin.

“My case of fuck-its was so bad, I said, ‘Let’s do it,’” Jack says. “It was the first time I’d ever done it.”

The pair got high that night, chasing tar on foil.

When Jack awoke the next day, he felt foggy and sick. At work that morning, he couldn’t focus. “I can’t be around this,” he thought.

Jack slept all day Saturday, woke up on Sunday, packed a bag and moved back into the Dana Point sober-living facility in which he and Cameron had met eight months before.

In the following weeks, Cameron resisted intervention attempts by Jack and other friends, but eventually, on April 4, Cameron called John C., his AA sponsor, and admitted he’d relapsed. “All right, let’s move forward,” John C. had said. “Let’s not look back. You relapsed; shit happens. Let’s get back on track.’’

The two met the next day, a Thursday, went to a meeting and planned on attending another meeting together on Friday night in the harbor, within walking distance of the boat. But Cameron didn’t show up. People began to worry when he didn’t answer his phone on Saturday and Sunday.

Around noon that Monday, Jack and a friend named Trevor walked down to the boat to check on Cameron. Police helicopters circled the harbor, responding to a man who died after crashing a boat into the jetty that morning. “Something doesn’t feel right,” Jack thought as he and Trevor approached the boat.

The boys called Cameron’s name. There was no response.

“Hey, buddy, what’s up,” Jack said, sliding back the wooden door to the cabin and looking inside.

Cameron wasn’t on the disheveled bed. He wasn’t on the couch.

Jack looked down and saw Cameron on the stairs leading to the door, face-down and shirtless with a belt around his arm.

“Call 911,” Jack shouted, but he already knew Cameron was gone.

Jack’s father, John, was at the scene when OCSD investigators arrived. Police were certain that fentanyl, or an analogue, was the cause of death. “Dealers don’t know how to dose the fentanyl,” the investigators told John, “so they up the dose till someone dies, and then they back off.”

The speed of Cameron’s death also pointed to fentanyl. According to the investigators, it appeared as if Cameron knew he’d taken too much and tried walking outside for help before collapsing.

Dunkle, who’s revived people from heroin and fentanyl overdoses, agrees. The difference, she explained, is that a heroin overdose can take an hour or more to kill, while a fentanyl overdose can kill almost instantly. Although the coroner’s report found no fentanyl in Cameron’s system, the plethora of fentanyl analogues mean that their presence is hard to detect. Jack and others report that Cameron couldn’t have picked up from his San Clemente dealer because he had no transportation; instead, they believe Cameron purchased that fatal dose from a Craigslist dealer who delivered the drugs to him.

“So many people that come out for treatment don’t care. Cameron didn’t have that feel,” John says. “When I first met him, I said, ‘Cam, you can walk in my house any time. If you need any help, let me know.’”

Numerous others say they wouldn’t be sober today, if not for Cameron. He was an active member of his community who slipped. This could happen to anyone.

* * * * *

There are two important lessons in Cameron’s story. One: Relapse is common. According to Dr. David Deyhimy, an anesthesiologist and medical director of OC Addiction Treatment Services and My MAT Clinic, 90 percent to 95 percent of recovering opioid addicts in abstinence-based treatment relapse within a year.

And two: It’s easy to access fentanyl-contaminated heroin.

In an article for Justice Quarterly, published Jan. 21, Christopher Contreras, a UC Irvine Ph.D. student in criminology, notes that rising drug use in a community correlates with rising violence. “Residential stability and high socioeconomic status do not necessarily buffer blocks with drug trafficking against rising robbery and burglary rates,” Contreras writes. “Instead, blocks with narcotics activity bring in serious, high-rate offenders, such as drug users, who may commit robberies and burglaries for drug money.” Additionally, because drug markets aren’t static, they can quickly shift from city to city. In other words, OC’s affluence won’t protect its residents from drug-related crimes if the spread of drugs continues.

Since police alone can’t be expected to solve the problem, harm reduction may be the best solution.

In 2017, when Dunkle had a central location to distribute naloxone, overdose rates decreased. However, when the OC Needle Exchange Program was shut down in January 2018, rates began rising.

“In 2016, we had 336 deaths. [In] 2017, we had 304 [255 were opioid related]. I literally bought all the naloxone that was distributed,” Dunkle says.

In that time, overdose-death rates in San Diego, Los Angeles and Oakland were higher than the year before. “Orange County was the only one that was down,” she says. “That in itself is an indicator of what happens when you have a centralized location for harm reduction.” Dunkle believes that three centralized naloxone distribution locations—one each in North, South and Central OC—would greatly reduce the county’s death rate.

Medication assisted treatment (MAT) has also proven effective. It combines the use of drugs such as Suboxone, a low-addiction-risk opioid, and methadone with behavioral therapy. According to Deyhimy, “When you stabilize with buprenorphine, all drug use decreases by 50 percent. These folks are getting the behavioral treatment they need, plus MAT.” Deyhimy added that patients undergoing MAT experienced a 50 percent abstinence rate after one year. Without MAT, recovering opioid addicts were 3.5 to 10 times more likely to die of an overdose.

Orange County currently offers MAT, but we could improve. “Five percent of U.S. doctors have a licence to prescribe [Suboxone], and of those, only a fraction actually prescribe it because insurance payments are very poor, and many doctors simply give up,” Deyhimy says.

Switzerland’s MAT program, which provided free injections of clean heroin for patients, effectively eliminated that country’s heroin crisis during the 1990s. Since 1991, there has been a 50 percent reduction of overdose death, an 80 percent reduction of incidence of starting heroin use and a 65 percent reduction of HIV infections, according to Ambros Uchtenhagen of the Research Institute for Public Health and Addiction. The medical journal Lancet concluded, “The harm reduction policy of Switzerland and its emphasis on the medicalisation of the heroin problem seems to have contributed to the image of heroin as unattractive for young people.”

Such an effort in Orange County would rely on a commitment from policy makers, police and the community to address opioid addiction medically. Otherwise, senseless deaths and crime will increase.

Unfortunately, this might not be enough. In the Feb. 23 issue of The Economist, a trio of Stanford public-health experts say that increasing naloxone distribution and MAT will decrease deaths by 4.1 percent and 2.4 percent respectively, over the next six years. Restricting opioid prescriptions, however, would result in a sharp increase in deaths, as people switch from pills to street opiates. The experts expect to record 500,000 overdose deaths between 2016 and 2025. According to the Economist article, “Even if America introduced all the policies likely to save lives, deaths over the next decade will drop by just 12.2 percent.”

Dr. Deyhimy introduced this bleak future at a town hall meeting in January. “We’re going to continue seeing lots of deaths each year in increasing number, and it’s going to be due to the fact that fentanyl is basically available on the internet,” he said. “Anyone can buy it.”

This is just a thought but do you think maybe if opioids weren’t so strictly strictly strictly controlled, if not so so illegal, that this crisis wouldn’t be such a life threatening crisis? That people can turn to doctors to get medical grade drugs (where the dosages are safe and the drugs are not cut with deadly additives) to feed their addictions under medical supervision where doctors will also have a chance to monitor and steer patients towards rehab when they are ready? That having access to these medical grade drugs might be cheaper than buying off the streets? So they don’t have to steal their parents money or burn away their children’s college tuition? How many lives would be saved then? The only opioid crisis there is is the trump administration and his obsolete and completely harmful prohibition tactics trying to roll public mentality backwards.

It was the over-prescription of opioids that started this crisis. Besides you are not going to stop addicts from seeking out a better high. Most addicts know about the dangers of fentanyl laced heroin, but they still seek it out because the high is much more intense than pure heroin.

The problem is much more complicated then most people realize, and has actually been made worse by the legalization of marijuana. Drug cartels, who are no longer able to make massive profits from marijuana production have switched their efforts to manufacturing heroin, fentanyl, and meth.

Yeah Michael, personally I think that heroin assisted treatment, like they have in Switzerland, could be a solution. Providing clean, free heroin in a medical setting would eliminate the need to purchase street drugs and in turn save lives.

Thank you for sharing Cameron’s story. It is important and each loss of life is a tragedy. I am very sorry for his family and loved ones. There is a lot more to the story of MAT than what you went into here. There is a lot of diversion and abuse of MAT as well. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t offer MAT and that MAT isn’t an important part of the solution, but it’s important not to paint a black and white picture of this problem and its solutions. The real problem is isolated, socially disconnected communities, lack of economic opportunities and the over-prescription of opioids you described that leads to people not able to access lasting recovery support. If they have that, then MAT can be an additional tool in long term recovery. But stories like this do help reduce the stigma around addiciton and get the stories out there. So thank you.

Hey SK, there’s certainly diversion of MAT drugs, and recovery itself is a challenge. I also agree with your thoughts about treating the socio-economic reasons that lead many people to get high. Thanks for the kind reply!

Craigslist. They deliver everything to your frontdoor. Fake IDs and passports too.

Maybe if they just legalize everything like weed. All the problems associated with it will go away. Or like frisco and portland. Set up safe clean places and give away clean needles for them to do it in. Don’t fight the problem. Cave in to it and support it.

The great band from Huntington Beach, China White, took their name from a song titled “Wasted” by a band called The Runaways. The lyrics to that song include these:

“Torpedoes in tuxedos

Got iron in their hands

Cotton sound, lost an’ found

Is in every crazy man

Lonely rain, bad cocaine

Doesn’t really matter

China white, don’t treat ya right

Sad you are so shattered”

This is according to the (former) drummer for the band, Joe Raffino.

Liam – Great work. Well researched, incredibly well written, insightful and informative.

This is tragic and not that unusual. The system failed this young man. “Treatment “ is nothing more than a faith based program from the 1930s that doesn’t work for most people. We must do better. It’s time for science based therapy like CBT and appropriate medications to care for people with substance use disorders.

So now I have a new hobby. I go onto Craigslist every day and search for all the drug listings – and click the “Prohibited” button. I don’t know who I’m inconveniencing, the dealers or the cops; but I’m pissing some people off. It only takes a few minutes. Sometimes twice a day. 🙂

CBD exceeded my expectations in every way thanks https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/blogs/learn/how-long-does-thc-stay-in-your-system . I’ve struggled with insomnia for years, and after demanding CBD pro the key mores, I at the last moment practised a full nightfall of calm sleep. It was like a bias had been lifted off the mark my shoulders. The calming effects were merciful despite it scholarly, allowing me to meaning afar uncomplicatedly without feeling woozy the next morning. I also noticed a reduction in my daytime angst, which was an unexpected but acceptable bonus. The partiality was a bit rough, but nothing intolerable. Comprehensive, CBD has been a game-changer in compensation my siesta and uneasiness issues, and I’m appreciative to arrange discovered its benefits.