In addition to the exhibit’s photos and footage, surfboards and gear, and artwork inspired by their wave riding, Lisa Andersen, Joyce Hoffman, Stephanie Gilmore and Rell Kapolioka’ehukai Sunn were honored in June at SHACC’s annual Ohana Gala, with a Lifetime Achievement award bestowed on the late Sunn, whose daughter and granddaughter accepted on her behalf.

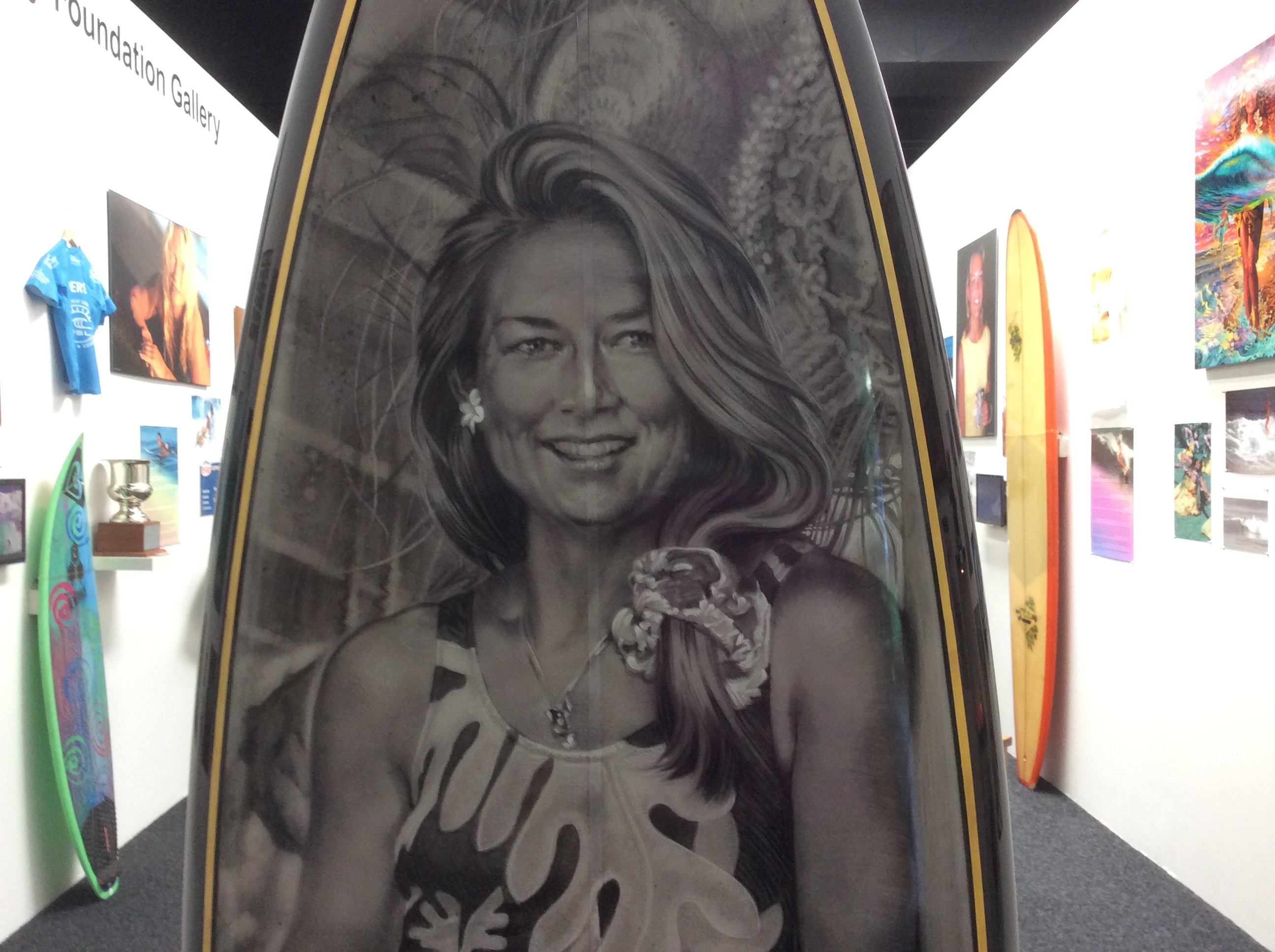

The Queen of Makaha—a poor town on Oahu’s west side where Sunn was born and lived her too-short life—is “one of the most influential and instrumental Hawaiian surfers of the modern era. She was a champion, barrier breaker, role model and matriarch,” begins SHACC’s bio.

Sunn competed in surf contests starting at 16 in 1966, entered her first men’s competition in 1975, and the following year launched the Menehune contest specifically for Makaha’s at-risk kids, which is still going today. She found boards for locals with pro potential. The all-around waterwoman co-founded the Women’s Professional Surfing Association, and waged a fierce 15-year battle with breast cancer.

Sunn was grace personified, whether on a board with arm raised or spearing fish for dinner or dancing hula or championing kids in her beloved hometown.

Aside from the life stories of these pivotal surfers, one of my favorite things about “Women Making Waves” is the variety of trophy design, including a breaking wave of green glass from G-Land and one honoring Sunn with this inscription in Hawaiian and English, “She cannot be caught for she is an ulua fish of the deep ocean.”

Of the four, Gilmore is the only one still competing; she is currently No. 1 on the Women’s Professional Tour. As a rookie in 2007, she earned a wild card spot that she rode to her first world title. With two wins already this year, the Australian may earn a seventh World Surf League (WSL) championship. Roxy’s current ambassador is active in ocean stewardship through Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and explores her creativity outside the water.

But Roxy wouldn’t be Roxy without Andersen. Just after winning her first world title at 23 in 1994, she urged designers to recut parent company Quiksilver’s boardshorts specifically for women to wear in competition before marketing them as-is under Roxy—a pair of Andersen’s signed shorts hangs in the exhibit not far from her first Surfer magazine cover, tagged with the simple statement: “Lisa Andersen surfs better than you.”

The four-time champ most admired male surfers with a fluid style (code for graceful?). “She could be so feminine on a wave yet so radical,” says onetime grom and Roxy teammate Meghan Abudo in Fearlessness, a book on her life Andersen proposed Nick Carroll write.

A tomboy nicknamed Trouble, Andersen ran away at 16 from her turbulent home in Ormond, Florida, and landed in Huntington Beach in the mid-1980s. The move was fraught with danger; nevertheless, she charged toward becoming the best. Even as she racked up trophies, Andersen struggled to win a world championship. It wasn’t until her daughter was born that she found the way within herself to get it done. The onetime runaway surfed like no one other than Lisa Andersen.

Hoffman, an OC surfer from Capo Beach and daughter of waterman Walter Hoffman of Hoffman Fabrics fame, dominated the sport in the 1960s. Known for her iron work ethic and intensive training, her incredible fitness and unflappable focus allowed her to master Banzai Pipeline, sending a message that no wave is off-limits to women.

A photo by Ron Church of an ABC Sports TV reporter interviewing Hoffman at water’s edge made me laugh, almost as much as the inscriptions on one of Andersen’s boards. The black-and-white shot is snapped just as the black-suit-and-skinny-tie clad newsman is overcome by whitewater rushing up to his armpits, while Hoffman calmly grins.

A print ad for Hoffman’s endorsement company Triumph has an ironic twist. “Tandem champs,” is the caption for a photomontage of her surfing the world and driving her Triumph Spitfire convertible wherever she goes. Though the campaign likely was working a pun for its girl-and-car superstars, the reference to a woman’s place in surfing being on a man’s shoulders in tandem-pairs events but otherwise dismissed reverberates 50 years later. The level of sponsorship Hoffman enjoyed then was an “aberration” for any gender; her trailblazing surfing was not.

In her keynote speech at the Ohana Gala, SHACC board member and co-founder of pro surfing Patti Patriccia recalled some hilarious misogyny. She and Sunn were surfing triple overheads on the North Shore in the early 1970s. Despite demonstrating their credibility on wave after wave, “Have you ever surfed naked?” was a routine question from the scant press that showed. Patriccia’s first offer of sponsorship came from an edible panties manufacturer.

All the slights and insults she recounted with humor at the awards ceremony fueled her. While still surfing, she devised a point system for qualifying women at events—other than posing for Playboy—and was director of the women’s division of the first pro tour. Patriccia became an attorney and an Emmy-nominated CNN journalist.

“Women are your consumers,” the author of WorkSmarts for Women: The Essential Sex Discrimination Survival Guide said to the surfing industry at the ball. “Don’t cut them out; don’t take their money and then spend half as much compared to the men when you sponsor women surfers and their contests. If my daughters and their friends are any indication, this generation won’t stand for it, anyway.”

She concluded by leading a gracious toast: imua!, a Hawaiian word meaning move forward together.

Executive director Glenn Brumage was so blown away by the event that he’s considering honoring women again at next year’s gala. Judging by the photo wall devoted to more than 50 other female competitors spanning decades in “Women Making Waves,” SHACC will have plenty of contenders.

“Women Making Waves,” at Surfing Heritage and Culture Center, 110 Calle Iglesia, San Clemente, (949) 388-0313; shack.org. Tues.-Sun., 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Through end of August. $5.

Lisa Black proofreads the dead-tree edition of the Weekly, and writes culture stories for her column Paint It Black.