People unfamiliar with the criminal-justice system in Orange County may suspect the process almost always functions correctly. Obeying constitutional rights, police and prosecutors pursue only guilty defendants. Juries issue verdicts while in possession of all key facts, and judges leave their biases at the courthouse door before ruling. Even if something goes awry, a court of appeal will take corrective action.

That rosy scenario is too often a fantasy, according to a 752-page report filed Aug. 26 by Assistant Public Defender Scott Sanders in People v. Daniel Wozniak, a gory double murder. For more than two years, Sanders has conducted an in-depth probe of courthouse shenanigans, making bombshell revelations and ruffling feathers. The findings aren’t speculative. Naming names and identifying wrongdoing with time-stamp precision, he’s made the case that law enforcement is plagued with dishonest characters willing to cheat even in death penalty cases and commit perjury to cover up corruption.

“There has been an impermissible pro-prosecution thumb on the scale of justice in this county for decades,” he observed.

This attack could be déjà vu for you. In January 2014, Sanders released his first provocative dispatch–in People v. Scott Dekraai–and set off quakes and aftershocks felt all the way to the East Coast. While critics complain the defense lawyer has manufactured a calamity, nobody can doubt the impact of his discoveries.

There have been abandoned murder trials; a felony conviction was overturned; tens of thousands of previously hidden records were released; deputies were caught committing perjury without punishment; prosecutors were booted from high-profile cases after feigning memory loss and ignoring ethics; officials acknowledged the existence of a jailhouse records system called TRED that contains hidden exculpatory evidence for hundreds, if not thousands, of defendants; legal scholar Erwin Chemerinsky declared a “constitutional crisis”; the national media, including CBS’s 60 Minutes, parachuted in; calls began for a U.S. Department of Justice investigation; and District Attorney Tony Rackauckas ordered ethics retraining and revamped policies, as well as created an external review panel.

Though Sanders’ latest motion is loaded with new, alarming details of alleged courthouse cheating going back three decades, there’s a likelihood it won’t cause as much commotion. Why? Judicial temperament.

In Dekraai, Superior Court Judge Thomas M. Goethals granted piecemeal approval of Sanders’ requests to obtain long-shielded records and to cross-examine deputies and prosecutors. With each development throughout 2014 bolstering the public defender’s stance, Goethals gave him more leeway, especially when he determined deputies Seth Tunstall and Ben Garcia had repeatedly lied on the witness stand and hidden crucial documents as a way to thwart Sanders’ inquiry. By March 2015, the judge saw a pattern that drew him, a former deputy DA, to a conclusion in the case: deputies and prosecutors can’t be trusted to obey basic ethical obligations. Goethals recused Rackauckas’ entire office and transferred Dekraai to the uncooperative California Attorney General Kamala Harris. That case is on hold while Harris fights her chore in appellate court.

Meanwhile, three floors down in Orange County’s central courthouse, where the Wozniak drama is unfolding, the public defender’s successes are being ignored or discredited. James Stotler, the first judge in the case, recused himself in January after admitting he’d been secretly rooting against Sanders. The county’s presiding judge sent the matter to Goethals, but prosecutor Matt Murphy objected, and Judge John D. Conley, a longtime prosecutor in the homicide unit that employs Murphy, took over.

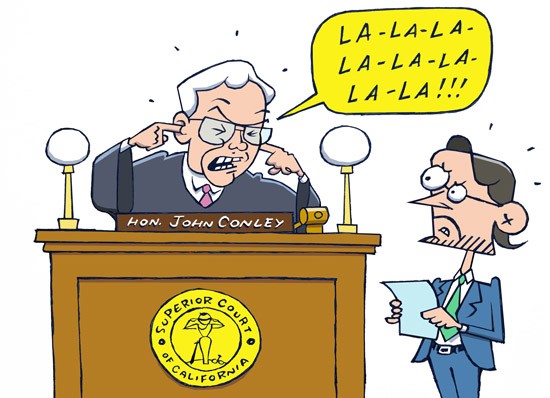

The difference in Dekraai and Wozniak, both in the penalty phase, is stark. Goethals kept an open mind to the possibility of law-enforcement cheating, gave Sanders an opportunity to prove his accusations and blasted the cheaters in rulings. Though Murphy remains unscathed on any ethics issue, Conley is pretending Goethals’ findings don’t exist, police-corruption allegations are a lark, and the public defender doesn’t need access to additional requested records and testimony. He has firmly stated he’s not allowing Sanders to go on any more “fishing expeditions.” While he has avoided Stotler’s mistake by chiding both Murphy and Sanders, this judge in recent weeks has handed the public defender zero victories and four major losses, including ones related to key TRED records.

During a multimonth, special evidentiary hearing in Dekraai, Sheriff Sandra Hutchens’ deputies (in league with the county counsel’s office) objected to sharing TREDs by arguing their release would wreck jail security. Goethals considered the claim, asked probing questions and determined the stance was baloney. (See “The TRED Deception,” April 1.) He ordered the documents surrendered because, for example, they showed deputies hadn’t been honest about conducting illegal jailhouse scams designed to trick pretrial inmates, such as Dekraai and Wozniak, into making self-incriminating statements, as well as that deputies had secretly rewarded snitches for pro-prosecution testimony, even though those deputies testified otherwise.

In another murder case, People v. Henry Rodriguez, even normally pro-prosecution Judge Frank F. Fasel rejected deputies’ security-concern claims to keep the informant records sealed from defense lawyers. Conley, however, bought the ruse and, in Wozniak, is allowing deputies to redact “anything they felt [is] dangerous for an informant or would expose the security procedures in the jail.” Keeping folks such as Sanders in the dark about the government’s employment of informants is, of course, how law enforcement managed to conduct these scams without detection for decades.

Perhaps worse, Conley appears unable to fathom the overarching point of Sanders’ motions: Deputies and prosecutors here have demonstrated they will hide or destroy jail records that benefit defendants, and therefore imposition of the death penalty in this climate inherently violates constitutional guarantees of basic fairness. For example, let’s say deputies repeatedly run scams to lure an inmate into committing crimes while locked up, but the target resists each time. To Sanders, that type of detail may or may not impact a jury considering death, but deputies have only used such information when they’ve succeeded in their trickery.

Conley isn’t worried mitigating facts for defendants aren’t emerging from jail and employed circular logic to make his point during an Aug. 7 hearing. “I look back in all my years of experience and think, ‘How much mitigating evidence has there ever been from the jail?'” he said, explaining that informants always try to get “bad things” on fellow inmates. “Isn’t your whole premise kind of speculative?”

Sanders replied, “The issue, really, in the sheriff’s department is when they are working, day in and day out, and they get the information that they don’t necessarily think is helpful [to the prosecution] or is favorable to a particular defendant–is that getting out [to juries]?”

The judge said he had “a problem” with the worry.

Such resistance makes Sanders believe Conley can’t be neutral and should recuse himself. In his recent Wozniak brief, he aimed at the judge, citing his use as a prosecutor of a dubious informant and illegally obtained jailhouse statements to win a conviction in the 1980s. According to the public defender, the case “suggests” Conley historically has shown “little interest in assessing informant issues implicating due-process rights and reforming the county’s jailhouse-informant effort.”

The public defender also wants Conley to submit to cross-examination about his work with snitch operations and will renew his request for recusal in coming days. Murphy must be smiling. The judge, known to deliver brutally terse one-liners, won’t likely comply. He aims to commence the October penalty phase for Wozniak with himself in control.

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.

I was offered a zero day prison sentence by Judge Makino, as Mark Geller, Detective Kim, Victoria Hurtado and Dawson and Officer Frei all from Irvine PD falsified 3-police reports and had me wrong convicted.

Another Detective that knew my case but didn’t work it, tried to assist me by getting me an in with the Conviction Review Board. Geller blocked me both times from within. My case was exonerated in February, 2018. Geller is a dangerous official. he cares nothing about following protocol. All he cares about is winning every case he takes. These true criminals destroyed my life and they have nothing to say afterward as to WHY???