Looking out the large windows from Jay Famiglietti's corner office at UC Irvine on a sun-drenched late-spring day, you take in an inviting deep greenbelt and, just beyond that, the green, green grass of Aldrich Park.

Contrast that with the view from the UCI hydrologist's new office at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, where Famiglietti is a senior water scientist. It's also serene and lovely here, but the hills cradling the sprawling facility are brown and tinder-dry heading into the always-gusty fall season.

“When I go back to Orange County, it is like Disneyland–everything is super-wonderful,” Famiglietti says from behind a small table at a JPL bustling because of a newly launched Mars mission. He has moved into a rental home in Sierra Madre while still holding onto his apartment above UCI.

“It's like the county is in a bubble,” he says of OC. “I leave Los Angeles County, and everything is brown. Then I get back to Irvine, and everything is green and lush. There is a little disconnect.”

See Also: 6 Videos on UCI/JPL's Alarming Groundwater Research

]

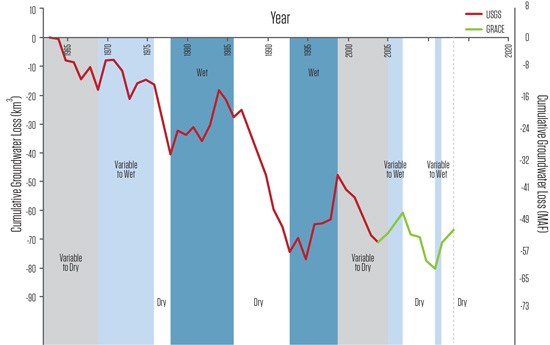

It's a disconnect Famiglietti has been talking about for a few years now, not just as it applies to the greenness of Orange versus LA counties, but to all of drought-sapped California, the United States and the world. He is convinced no amount of melting snow and torrential rains can bring California to the levels of fresh water we once enjoyed because as low as the lakes and rivers are, it's even more dire underground, from where most of our life-sustaining water comes.

Research Famiglietti has led or participated in is sobering. Should California keep drawing water out of the Central Valley ground at the rate it is now, the massive aquifer will be tapped out in “maybe 50 years,” according to the professor. “With more rains, maybe longer.” Orange County's imported water, which accounts for about half of what we consume, is in jeopardy thanks to over-pumping. The Colorado River Basin–which supplies water to 40 million people and 4 million acres of farmland in California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming and Colorado–lost more than 13 trillion gallons of water in less than a decade. Cities and farmers are sucking up a combined 15.6 cubic kilometers of water annually from the Ogallala aquifer, which stretches from South Dakota to Texas. The worst spot on the planet for groundwater depletion is the Upper Ganges, which irrigates crops in both India and Pakistan. Between 2003 and 2009, one of the world's great river basins–the Tigris-Euphrates, covering a swatch from eastern Turkey to western Iran–lost 144 cubic kilometers of fresh water, about the volume of the Dead Sea. Coastal areas of China, Thailand and Indonesia are dealing with a disastrous double whammy: ground sinking because of overpumping as sea levels rise.

Meanwhile, the global demand for fresh water is only going to grow, based on United Nations projections that say the world's 7 billion population will rise to 9 billion by 2050.

That's why Famiglietti is hellbent on spreading this message: We absolutely have to better manage the groundwater we have left, to do more with less. Perhaps his mission has not yet made him a household name à la Al Gore, but give Famiglietti time. An Inconvenient Thirst, anyone?

* * * * *

The UCI professor of Earth-system science and civil and environmental engineering has worked so hard to get the word out far and wide that Audrey Kelaher in the School of Physical Sciences dean's office politely asked him to create a website (JayFamiglietti.com) separate from the school's just to round up the links to his op/ed pieces for such outlets as the Los Angeles Times and Huffington Post; articles in The New York Times and elsewhere that quote him and his works; video clips on CBS, CNN and a TED talk; his constantly updated Twitter feed; and much more.

Reading the headlines of all those links, one might be tempted to brand Famiglietti the planet's next great sage of environmental doom, something that is reinforced on a canvas portrait that leans against a wall near Famiglietti's since-mothballed UCI office. It has his silhouetted mugshot next to text with his takeaway line from Jessica Yu's 2012 documentary on the world water crisis, Last Call at the Oasis (which now belongs to Participant Media's progressive channel Pivot).

Picture the scene: Farmers, agricultural officials and experts such as Famiglietti are meeting in Fresno to talk water or, rather, the lack thereof. “Let me be perfectly clear about this: California faces a water crisis of potentially epic proportions,” the professor tells the assembly. “You know, how we respond today will define who we are tomorrow.”

Polite claps, followed by brief cuts to other stakeholders saying we need more storage, more money to pay off farm debt, and more conservation and efficiency, the latter sparking off a furious debate, with one speaker grabbing the microphone away from another and associated back-and-forth vitriol.

Yu then shows us Famiglietti, slumped in his folding chair with his arms crossed, a look of disgust on his face. Next, we see him up close, in talking-head mode after the Fresno meeting.

“They wanted to make a statement that we do face a crisis now of epic proportions, and I said that. Um . . . and I'm not sure that it really resonated, which to me is a little startling. We need a plan, and we don't have one. And it is complex.”

He then utters the words that are on that picture of him at UCI: “We're screwed . . . yeah.”

Story continues on page 2.

[

Growing up in Providence, Rhode Island, Famiglietti did not dream of becoming a hydrologist. He wanted to be a veterinarian. “But I discovered in college I perhaps did not have the discipline to do well in pre-vet studies,” he explains. “I wandered into geology class and loved it.”

He considered graduate work in geophysics, in particular plate tectonics, but he “had been an environmentalist at heart since I was very young and the birth of Earth Day” in 1970. At school and in the Boy Scouts, conservation was a big deal, especially when it came to cleaning up Rhode Island's chronically polluted rivers.

Famiglietti received his bachelor of science degree in geology from Tufts University in 1982; two years later, he obtained a masters of science in hydrology from the University of Arizona. “It was natural that when I was looking for a career, I looked at earth science and gravitated toward water,” Famiglietti says with a shrug.

A master of arts and Ph.D. in civil engineering from Princeton University followed, in 1988 and '92 respectively. He was a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton and at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in 1992 and 1993. The following year, he joined the Geological Sciences Department faculty at the University of Texas at Austin, where he helped launch a climate program and the Environmental Science Institute.

He left the Lone Star State to join the UCI Physical Sciences Department in 2001 and was the founding director of the UC Center for Hydrologic Modeling in 2009. His years of important research and communicating about water and climate change led California Governor Jerry Brown to appoint him to the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Control Board in January.

“I think he wants more scientists on these boards,” Famiglietti told the Los Angeles Times' Patt Morrison, who'd asked why Brown appointed him to the post that pays a $100 per diem. “I feared it might be just a bunch of permit requests, but I learned a lot about the Santa Ana River basin. I want to bring an understanding of how it all works together and how it's changing.”

See Also: Water Wars: 9 Global Hot Spots

* * * * *

When Famiglietti first heard about GRACE, he didn't think it would work.

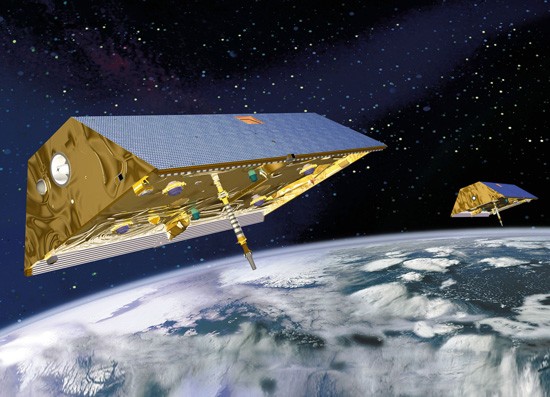

He was at the University of Texas at Austin when he was treated to some “salesmanship” about JPL's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, which has NASA satellites measuring the Earth's ice, water and gravity from space and calibrating the results with monitors all over the blue planet.

“I thought they were overselling it,” says Famiglietti, conceding he did not “appreciate the risk or scientific reward” of GRACE when it came to his groundwater research. But after having then-U-T graduate student (and fellow GRACE skeptic) Matthew Rodell “dig into it,” both were surprised to discover changes in underground aquifer water levels could indeed be measured from space. It has to do with changing water flows and the weight of water . . . you know, science-y stuff.

This became a game changer in the world of hydrology. Rodell, who has authored or co-authored several papers with Famiglietti and other academics based on findings from GRACE, is now the laboratory chief with NASA Hydrological Sciences at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

With GRACE, Famiglietti has researched the depletion of groundwater in California's Central Valley, the Colorado River and the Middle East. Thanks to this and our obvious-to-everyone drought conditions, he has not encountered the kind of criticism that still follows Al Gore when it comes to climate change.

“They really can't deny this is happening; they can see it,” Famiglietti says. “In the Central Valley and Coachella Valley, the water table is dropping. The ground is sinking. We don't see snow in the mountains. So it's a little less of a struggle to convince people.”

Famiglietti packed up his UCI office and moved to JPL because GRACE has become so key to his continued research. And he has been inspired by NASA's approach to scientists like him. The federal agency actually encourages pitches for funding varied scientific projects because, frankly, it keeps NASA relevant come budget time.

“I moved here in part so we can accelerate these models that we develop with satellite observation to really provide the best available information,” Famiglietti relates. “We need to say this is what is happening and not advocate for any one position. Just get everyone to pay attention along with us.”

* * * * *

The open ears to Famiglietti's research may have something to do with his feeling the pain (to borrow the line of Gore's old boss) of California's farmers. A newly added five-minute video addendum to Last Call at the Oasis shows him driving along the Golden State Freeway in Central California, passing those signs on plots of empty farm land that state such things as “Stop the Congress Created Dust Bowl.” You sense he hates the politicization of water but understands it deeply just the same.

“The worst place for water right now is California,” he says back at JPL. “It's ground zero. And then you have the whole food thing, the plight of the farmers. It is difficult. They take pride in setting the nation's tables, and the No. 1 thing they need is water. And we just don't have enough water. That's our future: We will never have enough water to do what we want to do in California. We have to prioritize.”

He called on academics and scientists to do a better job of communicating to farmers. “We need to build a relationship with farmers. The thing we need to figure out is sometimes as scientists, we're perceived as arrogant. We have to make people see now that we are here to help them.”

That, he said, is his No. 1 goal in Pasadena. “We have to tell [farmers] we want their input; we do not want their money. We want to be viewed as independent. Hopefully, there is enough NASA funding to do that.”

As we spoke, Famiglietti descibed a new NASA mission that will launch in January with a goal of bringing back data that will help inform farmers of how to more efficiently irrigate crops. The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) mission will also identify areas prone to flooding for mapping and, possibly, an early detection system. He hopes to use aircraft to expand the research and eventually develop methods for precisely delivering the optimal amount of water and nutrients to a plant, seedling or tree.

He guesses that his future research could eventually help agriculture realize as much as a 20 percent savings in water. The idea will be to pass along the vital information that farmers need “right away,” although the data will have to be thoroughly checked and calibrated with monitors on the ground.

“If we save even a half a percent of water” for large water users, “they will see what we're doing as economically justified,” Famiglietti says. “That would provide a lot of water for a lot of people.”

See Also: Mr. President, About That Water Crisis…

[

Another group Famiglietti hopes to help these days are water policy makers, whom he politely describes as somewhat underinformed about their subject.

“We need to improve our methods,” he says. “The best job we can do is create predictive models. We need a framework to evaluate different sources in the future.”

At meetings and conferences, he finds that people in agriculture, industry and water supply are “much more knowledgeable” about dwindling groundwater supplies than he might have assumed going in. “Water is managed extremely well in Southern California,” Famiglietti points out. “Water-district managers really have a difficult job. In general, they are providing water to all these people in a semi-arid region. Now, it is near-impossible. They are really in a tough situation.”

When most people think of water levels, they look at a lake or river and visualize a set mark as they would a bathtub ring to determine whether the amount of water is up or down. But where you can see it is not where most of the water is. Most is below ground, and it's unmanaged. “It's the Wild West,” Famiglietti explains. “There's a ton of money to be made in controlling it.”

He's pleased to see the final piece of the wet puzzle–residential users–are finally waking up to the fact they must do more with less water.

“I think it's very cool. I'm very excited about that. A lot of people, when they hear we are working with the NASA satellites, like it when we inform them about the work we are doing,” he says. “We need to visit with more people and let them know observatories and satellites are making a difference for earthlings.”

See Also: The Jay Famiglietti Reader

* * * * *

Courtesy Jay Famiglieti, NASA/JPL-Caltech, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and University of California, Irvine

In several chats with the Weekly, the water warrior always followed his dire warnings with the same word: hope. “There's always hope. We can change. We can adapt,” he says at one point at JPL. “I do think we'll respond in a good, thoughtful way.”

Famiglietti pauses a beat. “Because we have to.”

He was so inspired by President Barack Obama's speech at the United Nations Climate Summit in September that he wrote a National Geographic piece based on it. “He ends so optimistically,” Famiglietti recalls.

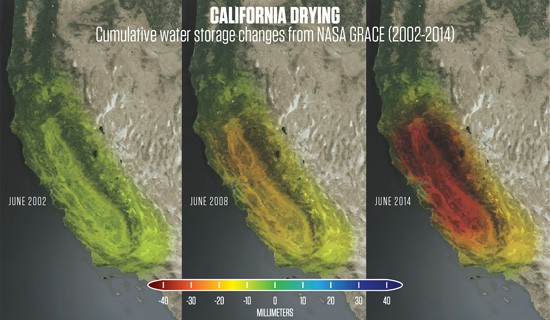

But it was that month's cover of Science that really excited him. For “The Drought You Can't See: Geophysical methods detect changes in water” stories, the journal borrowed an image the professor and his UCI team created of California as viewed from space, with an eerie red center extending from north to south. Beams Famiglietti, “It's like being on the cover of Time magazine for scientists.”

As he is quick to point out, this country has set deadlines before to achieve what first seemed impossible. (Hello, moon). “The same kind of commitment,” Famiglietti says, “is needed for clean drinking water.”

[

Anyone who observed the unsuccessful bids (so far) by the Orange County powers that be to build a 24-hours-per-day international commercial airport or extend a toll road through a state park in South County knows the routine. First come the “official” studies that show a problem exists, then the revelation that the only viable solution has been found, then the “official” praise from an organization legitimizing the studies and solution, then the push polls showing a majority of residents support the supposedly only viable solution, then the supportive Orange County Register editorial, and finally the building plans that were probably drawn up before the first study came out.

It's déjà vu all over again when it comes to dotting our coastline with desalination plants, which convert saltwater to drinking water. The Orange County grand jury issued a report in June that states water agencies should immediately start plans to build large desalination plants all along the coast. Four such plants are already in the pipeline in Southern California, including a 50 million-gallon-per-day facility in Huntington Beach that is in the final stages of permitting.

The grand jury claims the “low-hanging fruit” of storage, recycling and water conservation “has already been picked.” While Orange County's much-lauded toilet-to-tap, groundwater-replenishment system deserves praise, it cannot produce enough fresh water to satisfy demand, according to the panel.

A couple of days later came the Register editorial “Desalination the Answer for a Thirsty County.” The Orange County Water District (OCWD) praised the grand jury in August for focusing on water shortages, revealed plans to expand toilet-to-tap and welcomed “exploring alternative water supply projects like ocean desalination.” A month later, Probolsky Research of Irvine released a poll showing that 69 percent of likely voters within the OCWD boundaries support construction of the proposed Huntington Beach desalination facility.

Famiglietti agrees the internationally recognized, state-of-the-art, groundwater-recycling facility is “one of the coolest places in Orange County. It's like Disneyland. It's on my list for anyone visiting here as one of the top 10 things to do in Orange County.” But it is “not a cure-all” when it comes to producing enough drinking water. “The reality of it is we can't get enough” sewage to produce the amount of water we need.

As for desalination, it “is something we may need to invest in,” especially if we keep sucking water out of the ground at the rate we do, “but that is down the line,” according to Famiglietti. “The first thing we need to do is the cheapest and easiest way, and that is conservation.”

Far from being an already-picked fruit, as those folks who could not get out of grand jury duty put it, conservation via fixed leaks, better managed underground sources and the replacement of water-sucking landscaping would take this state and nation to water sustainability without having to resort to the horrors of desal, maintains Famiglietti, who also supports incentives rewarding those who curtail water use.

He points to the “unintended consequences” of desal plants, which consume large amounts of power to push water through a membrane, pollute the ocean with warm water and highly concentrated brine, and trap and kill marine life. Think of it like this: We'd be producing vital water and crops at the expense of vital oxygen and seafood.

“There are legal issues that come with killing marine life, which you will do,” Famiglietti says of current desal technology. “You will be affecting the whole state's ocean ecology, not only at your immediate coastline.”

Told of an environmentalist who predicted years ago that solutions to challenges such as water shortages will come once entrepreneurs figure out how to make money off them, Famiglietti replied, “I'm all for that. Smart people and creative people driving the green economy is a good thing. The problem is you want to do the right things with the money.”

* * * * *

When you have a conversation with someone who mentions things people can do on a micro level to help mitigate a macro problem, you naturally think of your own life. For me, I look at my front lawn and backyard pool when it comes to using less water. So, professor, do I need to replace my grass with succulents? “It could come to that.”

How about my pool? “Perhaps if you shade the pool so water does not evaporate as quickly. There have actually been studies that show pools do not use as much water as landscaping.”

He then thinks of his own lifestyle. A $250 residential water bill in Sierra Madre convinced him he needed a more efficient sprinkler system. Heading to a town meeting one evening, he watched a neighbor using a high-pressure nozzle attached to a garden hose to a push leaves off the driveway.

“I never did say anything to him, but I did go back and write this [angry column],” Famiglietti says.

Maintaining lawns and gardens sucks up far too much water, he says. But worldwide, agriculture requires 80 percent of the fresh water. We need to eat, and the population is not getting any smaller.

“There is room to improve efficiency,” Famiglietti says confidently. “Around the world, we could conserve 15 percent to 20 percent without doing that much.”

He's impressed that water managers managed to keep Orange County as green as it is for as long as it has been, but now the time has come for a paradigm shift, the professor professes.

“I'd rather it be less green over a longer period of time,” he says. “I think we're starting to see places like that in Orange County. Being too green is not green at all. This is what we probably need to come to terms with.”

See also:

JayFamiglietti.com

An Inconvenient Thirst: 9 Global Hot Spots

An Inconvenient Thirst: Jay Famiglietti Reader

An Inconvenient Thirst: Famiglietti's Itinerary

An Inconvenient Thirst: 6 Videos on UCI/JPL's Alarming Groundwater Research

Follow OC Weekly on Twitter @ocweekly or on Facebook!

Email: mc****@oc******.com. Twitter: @MatthewTCoker. Follow OC Weekly on Twitter @ocweekly or on Facebook!

OC Weekly Editor-in-Chief Matt Coker has been engaging, enraging and entertaining readers of newspapers, magazines and websites for decades. He spent the first 13 years of his career in journalism at daily newspapers before “graduating” to OC Weekly in 1995 as the alternative newsweekly’s first calendar editor.