Families removed from their homes. Children separated from their parents. A race of people accused of being terrorists despite no evidence. People losing their stores, houses, farms and livelihoods.

No, you’re not reading newspaper headlines from July 2019.

It’s post-1941 in Muzeo Museum and Cultural Center’s current exhibition, “I Am an American: Japanese Incarceration In a Time of Fear.” It researches and examines the time period shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, when the federal government created policies targeting legal Japanese American citizens (many of them immigrants) that ugly mirrors what’s currently happening to those termed “illegal” at the border.

My 20-year-old uncle, William Hasenfuss Jr., was one of the first Americans killed during the attack on Dec. 7, 1941. He was one of the 2,335 American service members (as well as 68 civilians) that died that morning, the instigation for America’s involvement in World War II. His name appears on a long list of fatalities near the start of the exhibition, amid images of listing and wrecked battleships with dark smoke pouring from them, implying that the reason behind Japanese Americans’ internment was what Japan did on that day.

The exhibit, which does its best to impartially focus on the facts, nevertheless does the tough research, revealing a long, forgotten and unsettling history of America’s racist treatment of immigrants: In 1894, the U.S. District Court ruled that the 1790 Naturalization Act allowed only whites to become American citizens; Alien Land Laws from 1913 to 1920 prevented Japanese Americans from owning or leasing land in the U.S.; the Immigration Act of 1924 ended immigration from Japan, and anti-miscegenation laws prevented them from marrying whites. Immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI arrested Japanese immigrant-community leaders, keeping most of them imprisoned throughout the war. The internment laws affected only the civil liberties of the nearly 128,000 Japanese Americans in the mainland U.S. They weren’t used against the even larger number of Japanese (about 158,000) in Hawaii at the time because it would have negatively affected the territory’s economics.

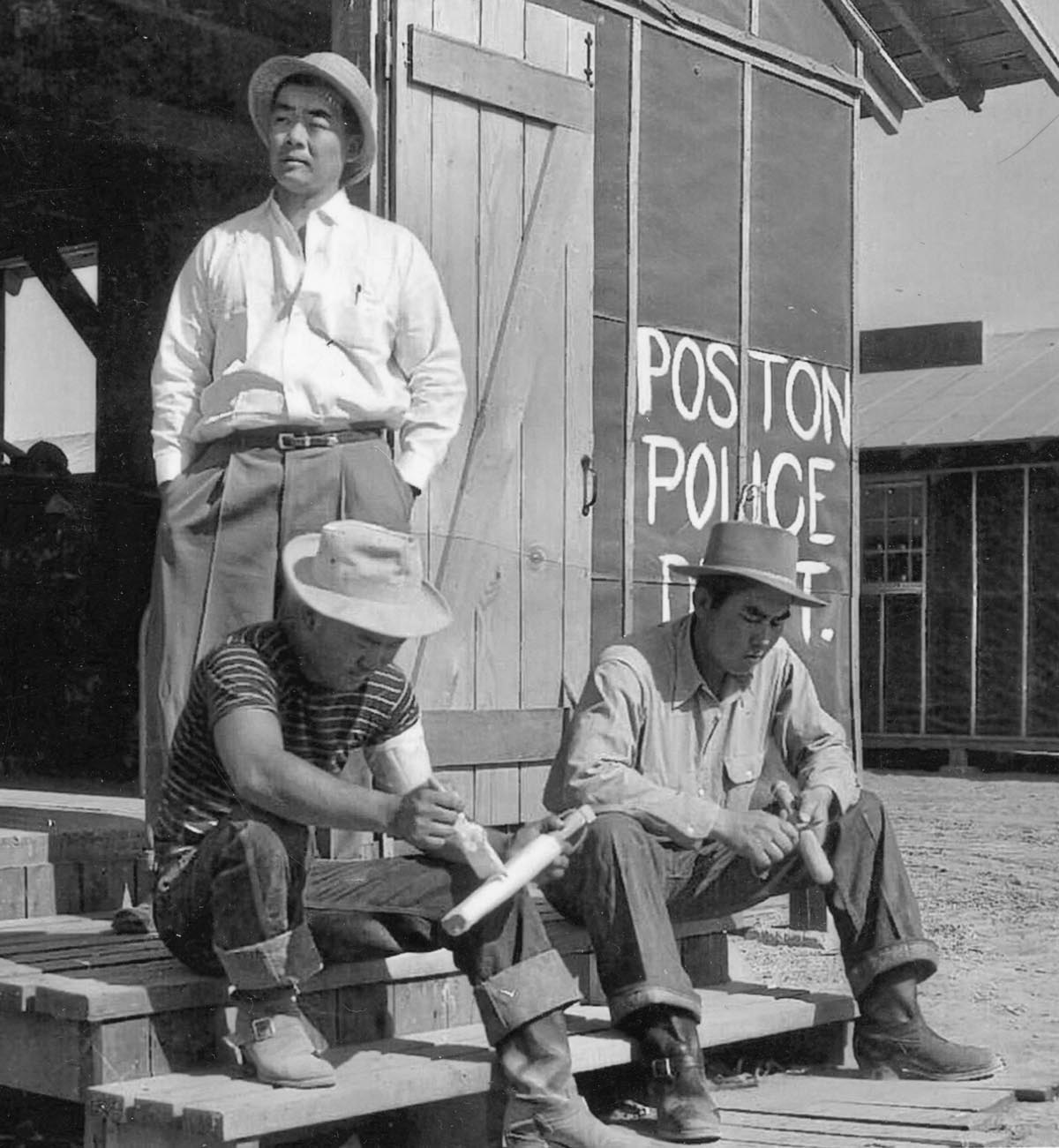

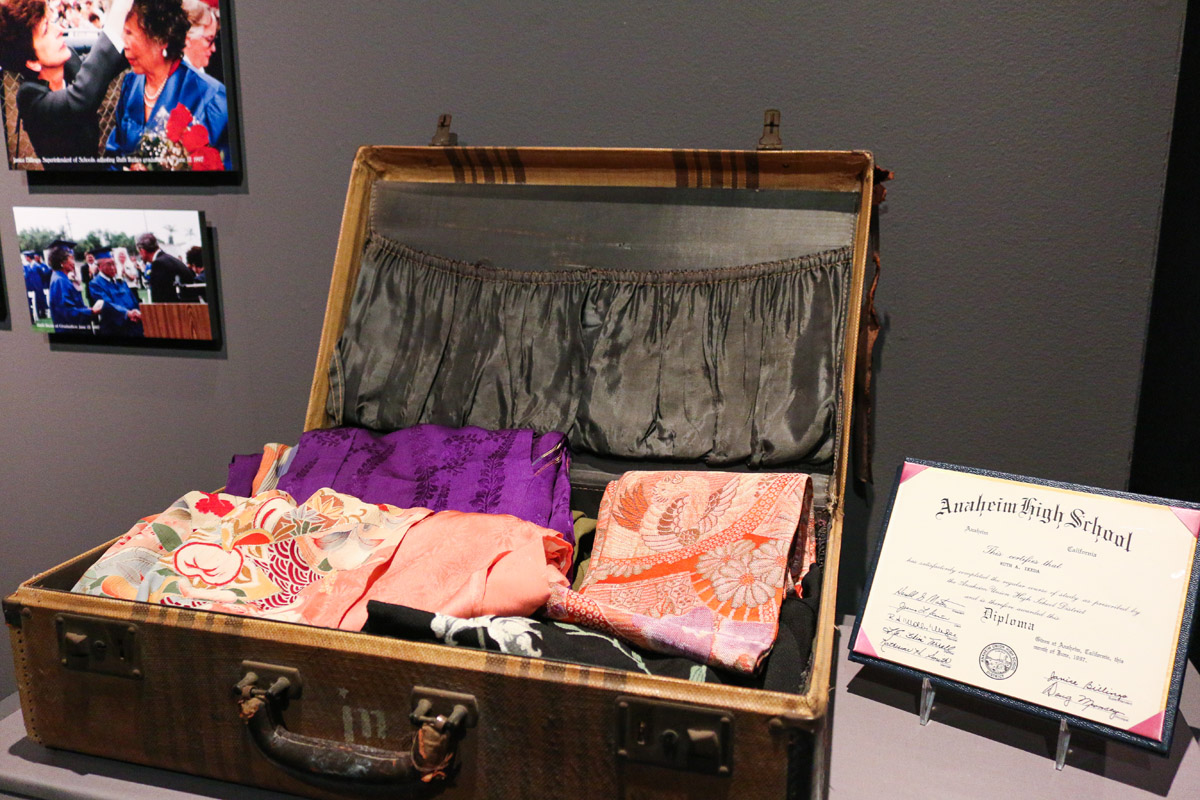

Muzeo opens the exhibit with curator notes about the role in the city of Anaheim of Japanese pioneers, who began to immigrate there in the late 1890s. It blends stories about Japanese American students at Anaheim Union High School and the Japanese Club, which lasted for only one year before the war started. The stories about the students being told at school that they were no longer welcome, then finding out they were being relocated to a concentration camp in Poston, Arizona, for the next three years, along with almost 18,000 others, is both moving and heartbreaking. (One fascinating historical note: The camp was built on Colorado River Indian reservation land. The tribal council wanted no part of their land to be used in what the country was doing, remembering that the government had done exactly the same thing to them less than 100 years earlier. Needless to say, the government didn’t give a damn and overruled them.)

Ephemera displayed includes suitcases, blankets, a handmade Go board and stones (a Chinese strategy game), knapsacks, wood carvings, toys, and artwork from the prisoners. There are also plenty of pictures taken within the camp, most of them War Relocation Authority photos, essentially propaganda that shows everyone smiling. Kids play basketball; the Girl Scouts have a popcorn booth. There are barn dances, games of volleyball, agricultural exhibits, and internee landscaping and building of the desert premises.

Space is devoted to the famous 442nd Infantry Regiment, composed almost entirely of Japanese Americans from the camps. According to the Go for Broke National Education Center, the internet home for info on the Army unit, it was the most decorated for its size and length of service in the entire history of the U.S. Military, “earning 9,486 Purple Hearts, 21 Medals of Honor and an unprecedented seven Presidential Unit Citations.”

Last, but not least, surviving members of 13 relocated Anaheim families were interviewed for the exhibition, including video testimonials from several elderly internees, all of which are also available online (www.anaheim.net/5404/Oral-History-Interviews).

I experienced one of many kicks to the conscience, contemplating my country’s unfortunate choices over the past three years as I stood inside the museum’s spare reconstruction of a 16-foot-by-25-foot wooden camp barrack, with its hard beds, potbelly stove, nails for clothes hangers, washtubs and dishes, and a bed sheet hung at the end of the room to offer a modicum of privacy to the family that would have lived there from the family that would have been in the next room.

“I Am an American” does a fine, thoughtful job helping us to stop forgetting the past. But what are we going to do when we remember?

“I Am an American: Japanese Incarceration In a Time of Fear” at Muzeo Museum and Cultural Center, 241 S. Anaheim Blvd., Anaheim, (714) 765-6450; muzeo.org. Open Wed.-Sun., 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Through Nov. 3. $7-$10.

Dave Barton has written for the OC Weekly for over twenty years, the last eight as their lead art critic. He has interviewed artists from punk rock photographer Edward Colver to monologist Mike Daisey, playwright Joe Penhall to culture jammer Ron English.

My grandfather was the conductor of the trains that took the Japanese Americans. They weren’t bad people some were angered but did as they were asked. After they were freed things never the same for them. Stores taken over , land taken away. Many moved to San Gabriel Valley. They began again AND MADE IT!

awesome

CBD exceeded my expectations in every way thanks https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/collections/cbd-cream . I’ve struggled with insomnia in the interest years, and after infuriating CBD because of the key mores, I lastly experienced a loaded nightfall of restful sleep. It was like a arrange had been lifted misled my shoulders. The calming effects were merciful yet scholarly, allowing me to roam afar obviously without sensibility groggy the next morning. I also noticed a reduction in my daytime apprehension, which was an unexpected but acceptable bonus. The cultivation was a bit rough, but nothing intolerable. Comprehensive, CBD has been a game-changer for my nap and solicitude issues, and I’m appreciative to have discovered its benefits.